1.3.6. Value Chain Governance - Overview

What is Value Chain Governance?

Value chain governance refers to the relationships among the buyers, sellers, service providers and regulatory institutions that operate within or influence the range of activities required to bring a product or service from inception to its end use. Governance is about power and the ability to exert control along the chain — at any point in the chain, some firm (or organization or institution) sets and/or enforces parameters under which others in the chain operate. The key parameters are:

- What is to be produced. This includes product design and specifications.

- How it is to be produced. This involves the definition of the production processes, which can include elements such as the technology to be used, quality systems, labor standards and environmental standards.

- How much is to be produced, and when. This refers to production scheduling and logistics. [1] [2]

Actors within the value chain set, monitor and facilitate compliance with “rules” that pertain to each of these parameters. The actors can be firms (buyers or producers) within the value chain or public or private institutions from the enabling environment. The same actor does not have to be responsible for setting, monitoring and facilitating compliance with the rules – combinations of actors frequently fulfill these responsibilities. Furthermore, different actors may exert more or less influence as one moves from local to global markets, and the scope of an actor/action's impact can be industry-specific or broadly focused.

Chain governance exists when some firms work to the parameters set by other powerful firms in the chain. [3] The firm that sets the parameters with which other firms in the chain must comply is referred to as the lead firm in the chain. The relationships lead firms have with their suppliers can either be helpful with respect to improving the competitiveness of the industry, based on a commitment to long-term, mutually beneficial relationships with suppliers, or they can be predatory and focused on realizing a quick profit in the short-term.

The need for lead firms to coordinate value chain activities has primarily come from two main trends. First, the trend towards outsourcing non-strategic activities that were previously performed in-house by large, vertically integrated companies has led managerial control to be replaced by the need for value chain governance. Second, product differentiation strategies and concern for meeting the growing number of environmental and social rules and standards set by external agents have led to the increased need for lead firms to control activities carried out by other firms in the chain. [1]

Why Governance Matters

Recent instances of toxic substances found in the U.S. food supply and other everyday products and stories of children laboring in sweatshops point to the importance of governance and of the control lead firms can and need to exercise over outsourced providers of both raw materials and finished products. Many firms do not own the farms and manufacturing facilities that make the products they sell; they take ownership of these products only when they arrive at their warehouses or distribution centers. However, these firms can and often do influence what happens at earlier points in the chain.

Understanding how and when lead firms set, monitor and enforce rules and standards can help micro and small enterprises (MSEs) and other firms in the chain better integrate and coordinate their activities. Governance is particularly important for the generation, transfer, and diffusion of knowledge leading to innovation, which enables firms to improve their performance and sustain competitive advantage. Awareness of the governance structure of a value chain can provide governments, donors and development practitioners with information about how best to provide MSEs with the training and technical assistance needed to upgrade their position in the chain.

Governance helps to determine the following:[4]

- Acquisition of production capability. Lead firms can be very demanding about reducing costs, raising quality and increasing on-time performance. Yet, along with high standards, lead firms also provide knowledge and support. MSEs learn by observing what their buyers are doing or in other cases, the lead firm will transmit best practices through embedded services or provide hands-on advice on how to improve production processes and producers' skills.

- Market access. Even as developed countries dismantle trade barriers, developing country producers do not necessarily gain access because chains are often governed by a limited number of powerful buyers. In order to participate in export manufacturing to developed countries, MSEs need to be on the radar of the lead firms of their chains because the lead firm frequently makes the decisions on where products will be produced and who will produce them. Producers need access to lead firms and can gain it only by learning how to communicate with the firms and produce to specification.

- Distribution of gains. The activities that reap the highest returns are usually found in intangible competences (R&D, design, branding) characterized by high barriers to entry that are frequently synonymous with holding the lead firm status in the chain. In contrast, developing country firms tend to engage in the tangible, production-related activities under terms set by the lead firm that have low entry barriers and thus low returns. It is important to know which activities in the chain bring in the most profitable returns and who engages in these value-adding segments. Understanding how a chain is governed provides MSEs and practitioners with valuable information on how to develop skills and with whom to develop relationships that would give them the flexibility and freedom to undertake additional functions in the chain, thus altering the current distribution of gains.

- Leverage for policy initiatives. Given the power lead firms have to impose product and process parameters on their suppliers, they are also excellent leverage points for the business environment to use to exert influence on what happens in their supplier firms. Understanding chain governance and the power of lead firms can assist local and global, public and private, government and nongovernmental agencies and practitioners to advocate for better labor and environmental standards or a more equitable distribution of gains.

Types of Value Chain Governance

The connections between industry activities within a chain can be described along a continuum extending from the market, characterized by "arm's-length" relationships, to hierarchical value chains illustrated through direct ownership of production processes. Between these two extremes are three network-style modes of governance: modular, relational, and captive. Network-style governance represents a situation in which the lead firm exercises power through coordination of production vis-à-vis suppliers (to varying degrees), without any direct ownership of the firms.[5]

- Market. Market governance involves transactions that are relatively simple, information on product specifications is easily transmitted, and producers can make products with minimal input from buyers.

- Modular. Modular governance occurs when a product requires the firms in the chain to undertake complex transactions that are relatively easy to codify.

- Relational. In this network-style governance pattern, interactions between buyers and sellers are characterized by the transfer of information and embedded services based on mutual reliance regulated through reputation, social and spatial proximity, family and ethnic ties, and the like.

- Captive. In these chains, small suppliers are dependent on a few buyers that often wield a great deal of power and control. Such networks are frequently characterized by a high degree of monitoring and control by the lead firm.

- Hierarchy. Hierarchical governance describes chains that are characterized by vertical integration and managerial control within a set of lead firms that develops and manufactures products in-house. This usually occurs when product specifications cannot be codified, products are complex, or highly competent suppliers cannot be found.

Image

Determinants of Governance Structure

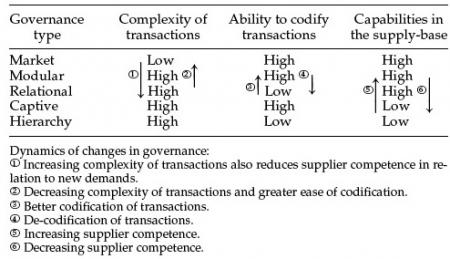

The form of governance can change as an industry evolves and matures, and governance patterns within an industry can vary from one stage of the chain to another. The dynamic nature of governance can be largely accounted for with three variables: the complexity of information that the manufacture of a product entails (design and process); the ability to codify or systematize the transfer of knowledge to suppliers; and the capabilities of existing suppliers to efficiently and reliably produce the product. Additional influences on the governance structure include the quality, stability, and power of the business enabling environment and institutions, as well as other sources of power in the chain, such as suppliers and consumers.

- Information Complexity refers to the intricacy of information and knowledge that must be transferred to ensure a particular transaction can occur.

- Information Codification is the extent to which lead firms can convert tacit, implied information and knowledge into explicit, concrete and situation-specific information and transmit it to producers effectively, efficiently and at minimal cost.

- Supplier Capability refers to the ability of suppliers to meet all transaction requirements. These may include quantity and quality specifications; on-time delivery; and environmental, labor and safety standards.

Dynamism in Governance

If one of these three variables changes, then value chain governance patterns tend to shift in predictable ways. For example, if a new technology renders an established codification scheme obsolete, modular value chains are likely to become more relational; and if competent suppliers cannot be found, captive networks and even vertical integration would become more prevalent. Conversely, rising supplier competence might result in captive networks moving towards the relational type, and better codification schemes set the stage for modular networks.

Image

The most common initial form of governance that lead firms establish with MSEs in developing countries is the captive form. In captive value chains, the lead firm (typically a global buyer from the United States or Europe) exhibits a great deal of control over the actors in the chain. In contrast, relational structures are the least likely to initially occur between developing country producers and global buyers due to the knowledge and skill gaps, as well as social and spatial divides. [7] [8]

The following are examples of changes in variables that result in a change in the type of firm governance:

- Captive to relational

- Captive to modular

- Captive to market

- Hierarchy to relational

- Hierarchy to modular

Other Contributing Factors

If the governance mechanism in an industry is not adequately explained through one of the chain governance structures, then an alternative factor, such as a strong institutional environment or other sources of market power, is likely to be at work.

Business Enabling Environment and Institutions: The business enabling environment incorporates the physical entities, including government agencies and nongovernmental organizations--such as multi-lateral agencies, industry trade groups, labor unions and advocacy groups--that set forth institutions. These institutions are defined as the rules that govern society, including laws, policies, standards and societal and cultural norms that impact the competitiveness of an industry and shape the forms and actions of entities in the business enabling environment. Institutions can be legally or voluntarily enforceable. The rules/institutions set by the enabling environment are derived, to a greater or lesser degree, by the beliefs, values, meanings and priorities embedded in the societies that create, fund and staff them. As a result, limits are placed on actions, and firms or managers that surpass those limits run the risk of sanction, creating pressure for firms to operate according to the norms and expectations of the societies in which they operate.[9]

The business enabling environment not only sets rules; it also creates resources to facilitate compliance with rules set by internal and external members of the chain. The enabling environment also acts as a “check and balance” system—when lead firms become too powerful or engage in predatory practices, institutions can place limits on these actions. For example, the power attributed to buyers such as Nike or The Gap is associated with their brands' reputations. When these firms' reputations were threatened by external activists' accounts of unethical labor conditions in their factories, the lead firms were quick to voluntarily improve their conditions. Later on, this frequently leads to mandated institutions to regulate social and environmental practices, as well as means to ensure, certify and assist factories with compliance.

Power: Power is the ability of a firm or organization to exert influence and control over other firms in the chain. At the firm level, power is accumulated, held, and wielded in different ways and in different amounts. Power can come from any part of the value chain structure, in many different forms. Within the chain, power comes from firms and the workers within the firms. Power within the chain can be divided into power exerted by lead firms or from suppliers. Outside the chain, power comes from institutions created by the enabling environment and consumers.[10] Those in possession of industry power actively shape the distribution of profits and risk through their activities.

Recommended Good Practices

Analyze chain governance to determine leverage points: where, how and when can practitioners intervene to effect systemic change and influence industry behavior. Analysis should seek to understand:

- Economic interests: Assess interests and incentives at aggregation points and determine how changes in the system will impact the benefits, profits, and power that are likely to accrue to lead firms versus suppliers.

- Social structure: Work with respected social figures, such as key farmers, chiefs and elders who can influence others to adopt or purchase new techniques, technologies, services or inputs.

- Competition and strategy: Changes in the level of competition or in lead firm strategies can pressure buyers, traders and others to change predatory or abusive behavior.

Encourage capability-enhancing governance at all levels of the chain. Supportive governance facilitates the social and economic development of all of the firms within the chain, rather than simply meeting the needs of the lead firm. Practitioners should work with lead firms, traders and input suppliers to set, codify and monitor rules and standards that will help make the chain effective, efficient and equitable for all parties involved. It is important to make sure that all parts of the chain understand the terms and meet the standards.

Facilitate the development of supporting markets. Technical assistance, training and business services are critical to helping suppliers improve their ability to meet customer/lead firm specifications and can be a primary avenue of intervention for practitioners. In addition to helping MSEs upgrade, support services can be provided to train other MSE service providers in compliance monitoring or to teach producers how to comply with standards. Though some programs are beginning to use buyers to reach greater numbers of MSEs, programs also may have to work with and mentor lead firms in transferring information and skills.

For More Information

For more information on governance and other GVC-related topics, see the websites and reports provided on the Global Value Chain (GVC) Initiative website (www.globalvaluechains.org) and Duke University's Center on Globalization, Governance & Competitiveness (CGGC)(www.cggc.duke.edu).

Footnotes

-

- Chain Governance and Upgrading: Taking Stock. Humphrey, J., and Schmitz, H. (2004). In H. Schmitz (Ed.), Local Enterprises in the Global Economy: Issues of Governance and Upgrading (pp. 349-381). UK: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited.

- Inter-firm Relationships in Global Value Chains: Trends in Chain Governance and Their Policy Implications. Humphrey, J. & Schmitz, H. (2008). International Journal of Technological Learning, Innovation, and Development, 1(3), pp. 258-282.

- Developing Country Firms in the World Economy: Governance and Upgrading in Global Value Chains, Humphrey, J., & Schmitz, H.; INEF Report No. 61 (2002). Duisburg: University of Duisburg.

- Humphrey (2002)

- Export-oriented Growth and Industrial Upgrading: Lessons from the Mexican Apparel Case, Gereffi, G.; World Bank case study for Uma Subramanian. January 31; 2005.

- The Governance of Global Value Chains. Gereffi, G., Humphrey, J., & Sturgeon, T. (2005). Review of International Political Economy, 12(1), p. 89.

- Governance and Upgrading: Linking Industrial Cluster Global Value Chain Research.Humphrey, J., & Schmitz, H.; IDS Working Paper (No. 120), Institute of Development Studies; (2005).

- Upgrading in Global Value Chains: Lessons from Latin American Clusters. Giuliani, E., Pietrobelli, C., & Rabellotti, R.; World Development, 33(4), 549-573; (2005).

- From Commodity Chains to Value Chains: Interdisciplinary Theory Building in an Age of Globalization, Sturgeon, T. In J. Bair (Ed.), Frontiers of Commodity Chain Research. Stanford University Press; (2009).

- Sturgeon (2009).