Systemic and Catalytic Change in USAID’s Economic Growth Policy

By: Nathan Martinez and Ishani Desai from the Economics Team in the Center for Economics and Market Development. This is the fourth in a series of blogs around the six principles of USAID’s Economic Growth Policy.

The United States Agency for International Development’s (USAID) Economic Growth (EG) Policy Framework lists six central principles to guide USAID’s economic growth programs. The third principle states that “programs must be systemic or catalytic.” But what is systemic change? According to the Policy, systemic change refers to strengthening market systems, improving policies and governance, and creating opportunities to achieve transformative and broad-based growth. If this feels quite extensive, it is because it is. Economies are complex and interconnected systems that best operate when all the pieces function properly. A logical place to start understanding this system is to consider whether all the major components of an economy function and, if not, what constrains them.

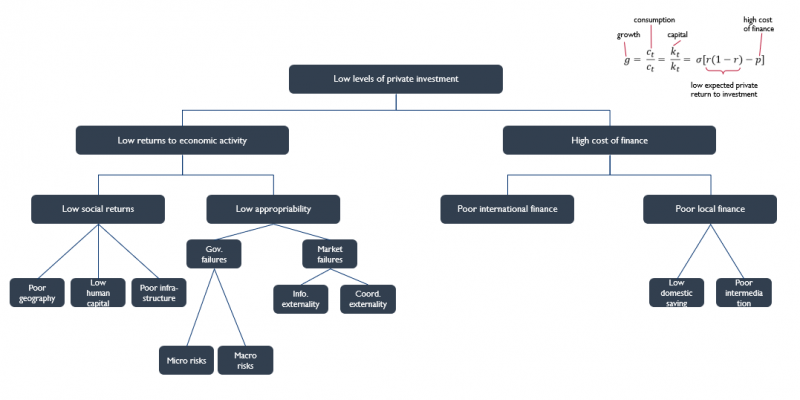

USAID and its interagency partner, the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC), each use a version of growth diagnostics to identify the constraints that deter enterprises and households from making investments and taking risks that would significantly increase their wealth. The growth diagnostic approach is based on the premise that there are certain inputs needed for economic growth. By applying a series of diagnostic tests across each of these inputs, development practitioners are able to identify where there are problems (see Figure 1 for a description of these inputs). Since the tests are applied systematically, users can measure the severity of each issue and prioritize the main constraints impeding systemic change.

Figure I: Growth Diagnostic Decision Tree Framework (Figure shows graphical representation of Growth Diagnostic Decision Tree Framework)

Image

As a next step, practitioners derive a logical causal story or “syndrome” to explain why these constraints exist. These explanations are informed by incorporating feedback held from stakeholder workshops where facilitators ask participants why they believe a certain constraint exists. A formal approach, such as MCC’s root cause analysis, may also be employed if there is time and resources. Typically, the identified syndrome is tied to political economy issues, such as the geographic and geopolitical syndrome identified in the USAID Inclusive Growth Diagnostic for Armenia.

While the growth diagnostic approach and the identified syndrome can lead to significant and valuable insights that inform better decision-making, it does not prescribe specific interventions. In the same way that diagnosis and treatment of a disease are separate medical functions, it leaves the ultimate ‘treatment’ of the binding constraints to other development practitioners, organizations and the host country government. As a result, the analysis does not attempt to incorporate political economy considerations, meaning it does not assess the political or practical feasibility of reform efforts targeting the constraints. Further research, such as a political economy analysis of the reform options, would provide a more comprehensive understanding of the types of interventions that would be both feasible and impactful.

But what is the point of undertaking this exercise if an organization does not have the resources or know-how to address the syndrome or undertake an identified reform? First and foremost, this exercise produces a public good. Further, organizations can strategically partner with governments and other actors who do have the necessary resources to alleviate binding constraints, ensuring all other interventions have the greatest chances to succeed. Another option is to only engage in interventions that have the greatest chance for widespread or catalytic impact. This will include activities that local actors can scale up; that USAID and partners can replicate widely; or that lead to changes in policies, regulations, or institutions that address the underlying issues.

For example, USAID/Tunisia’s Business Reform and Competitiveness Project (BRCP) used a flexible and adaptive approach to identify key constraints to the ability of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (SMEs) to grow and create jobs. At the start of BRCP, its formally structured pre-employment training was not achieving the expected results. In response, the project started working with enterprises to identify market opportunities with high-growth potential. BRCP then provided technical assistance, such as increased access to finance and improved capacity within the enterprise’s human resources departments, that allowed enterprises to meet this demand and hire more workers. The buyer-led approach enabled BRCP to scale the intervention to different sectors and regions, resulting in the creation of over 23,521 full-time jobs.

The solutions for developing systemic or catalytic programs will vary by country and sector, and require thoughtful planning, flexibility, and a little bit of luck. The question now is how to best work with others to achieve these goals?