Beyond Greasing Wheels: Corruption and Inclusive Growth

This post, authored by William M Butterfield, the Entrepreneurial Environment Team Leader in the Center for Economics and Market Development at USAID in Washington, is the third in a series of blogs around the six principles of USAID’s Economic Growth Policy.

USAID’s Economic Growth Policy positions inclusive, sustained, and resilient economic growth as central to development. In a previous post, I expanded upon the first principle of the Policy, enabling our partners to become self-financing. The Policy’s second principle requires that programs prioritize inclusion, sustainability, and resilience. This post reviews this principle and specifically focuses on the importance of inclusive growth and its relationship to corruption.

Growth can — and should be — inclusive and is necessary for poverty alleviation

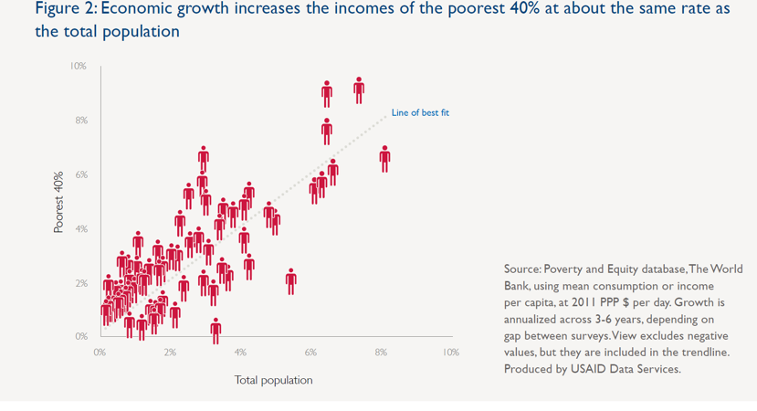

On average, economic growth is good for the poor as the income of the bottom 40 percent of a population grows at about the same rate as average incomes (Figure 2 in the EG Policy). With robust economic growth, inequality in most emerging economies has declined or remained unchanged between 2007-2015 (though the impact of COVID-19 may exacerbate inequality). And importantly, addressing sustainable poverty alleviation simply isn’t possible without economic growth.

Image

High levels of inequality slow growth

However, past certain thresholds, inequality starts to become structural, reducing economic growth rates. Fragile states often descend into conflict when citizens perceive economic outcomes as inequitable, and conflict almost always reverses growth. Even in less fragile settings, increased inequality can erode social cohesion. High levels of inequality are normally marked by small, yet powerful, interests that can exert outsized influence on policy and government officials, which results in less competitive markets and systematically slower growth. Low state capacity is a fundamental characteristic of underdevelopment and poverty, and weak institutions lend themselves to institutionalized corruption.

Endemic corruption is a key factor that slows economic growth. It is also related to inequality because it involves the active exclusion of large and critical segments of the population from economic opportunities. Weak state capacity and institutions, high levels of corruption, and low economic growth are all interrelated - each is both a symptom and a cause of the other, consistent with the EG Policy Framework.

Corruption lies at the heart of structural inequality

As stressed in my previous post, competition and commercialization are critical for market systems and enterprise-driven development. Political and bureaucratic corruption often function to limit competition against incumbent and powerful firms, whereby these actors exchange illicit payments for protections and targeted enforcement against existing or potential rivals. They may also exchange illicit payments for tax avoidance or targeted exemptions, which disadvantages nascent, minority, or women-led firms who could be more productive and create more jobs. (For a cinematic portrayal of this in action, check out the recent film “The White Tiger”).

I also stressed in that post how the cost of regulatory compliance is not always consistent across firms. Often, complex rules are a feature, not a bug, of the business enabling environment because they can facilitate corruption. More agencies and additional steps required for doing business create more opportunities for hold-ups and illicit payments. A lack of, or limited transparency around, compliance requirements also creates fertile ground for arbitrary fee-charging. Data from the World Bank’s Enterprise Surveys shows that increasing the time managers spend dealing with regulation increases the likelihood the average firm will pay bribes.

There is also an important gender component to consider when it comes to corruption. For example, the World Bank’s Enterprise Surveys found that women-owned businesses were less likely to pay bribes. But this is not because women are necessarily less corruptible compared to men. “It’s because women are less likely to be members of, or trusted by, existing patronage networks (which are predominantly male).” We need further evidence to best counter corruption and equip both women and men with technology-based solutions.

How can donors help combat corruption?

Technology is one of the drivers of economic growth per the EG Policy. It is also key to reducing corruption through new forms of e-governance that eliminates the need for interpersonal interactions (limiting contact is also important in pandemics). In Ukraine, the pilot of the USAID-funded e-procurement platform, ProZorro, helped the national government cut costs by 12 percent while perceived corruption decreased from 59 percent to 29 percent from 2016–2017.

While these interventions to equip governments with digital technology solutions for service delivery remain critical, many government digital technology projects fail. Governments often automate processes through e-services but fail to see the reform through for effective implementation (e.g. staff training, fixing glitches, tutorials for users, officials resisting automation, etc.). Technology transfer alone does not change organizational culture toward a focus on performance and customer service. What is required is often a comprehensive change in the incentives faced by the bureaucracy and local law enforcement. Therefore, programs that focus on the “demand side”, or building the capacity of individuals and groups to recognize and respond to corruption and poor governance are just as important.

For example, the USAID Nepal Private Sector Engagement Assessment found that Nepali government dysfunction and corruption “emanates from the supply side, as well as from the demand side. On the demand side, citizens who were adversely affected by the economy’s poor performance have not yet initiated effective demand on the incumbent political leadership and the bureaucracy for them to undertake reforms and adopt more sound economic policies. The weak advocacy for change in the country is partly due to the absence of young, educated, and informed Nepalis, many of whom migrated to work abroad because of the limited, enabling employment opportunities in the country.”

Technology can play a major role here as well. For example, the 2021 World Development Report covers the “I paid a bribe” online initiative launched in 2011 by the Janaagraha Centre for Citizenship and Democracy in India, which “has developed into one of the largest crowdsourced anticorruption platforms in the world. This tool collects citizens’ reports of corrupt behavior and merges them with geospatial data to highlight problem areas. In doing so, it empowers individuals, civil society, and governments to fight corrupt behavior.” The report also covers the growing use of crowdsourced data, web scraping, and social media to fight corruption and receive real-time feedback on the impact of reforms.

A Focus on Empowerment

The EG Policy “recognizes that an emphasis on human rights and dignity, individual liberty, and democratic accountability is a foundation for economic growth and development.” Because corruption deprives individuals of equal access to market-based opportunities, it robs many of them of their livelihoods and basic human rights.

Let’s think about how we can effectively combine and integrate technology-based solutions with a focus on building citizen demand for better governance and ending corruption so we can address the root causes of inequality and advance more inclusive economic growth.