6.9.1. Resource 1: Current State of WEEGE Data

Overview

This document outlines the opportunities and challenges that USAID staff are likely to encounter as they gather, analyze and share data related to women’s economic empowerment and gender equality (WEEGE). The last several years has seen rapid growth in relevant gender data and reporting from governmental, international and civil society organizations. There has been an increasing recognition that the economic lives of women—as consumers, customers, entrepreneurs and businesswomen—must be taken into consideration. There are several actors contributing to research relevant to WEEGE, many of which are referenced in Resource 2: WEEGE Monitoring, Evaluation and Learning (MEL). The increasing recognition of the importance of WEEGE work has brought more resources to the table, while also showing that, due to historical inequities in data and resources, there is still much progress to be made. Prioritizing MEL planning from the outset of any development initiative is critical to assessing the effectiveness of WEEGE programming, including which aspects of project design and implementation should be avoided, replicated or scaled.

This resource begins by introducing the opportunities for impact in WEEGE. It then reviews challenges and solutions to WEEGE data collection and use (including gender bias in data collection systems), the complexity of the concept of empowerment, and tensions between harmonization and customization of WEEGE data.

Opportunities Related to WEEGE Data

The recent growth in WEEGE-related research has brought forward many opportunities for further impact, presenting unique opportunities, as summarized below, to develop strong WEEGE MEL agendas that capture women’s economic empowerment and changes in equality. The following opportunities present openings to ensure that WEEGE is integrated and prioritized at all levels of data gathering and learning.

Influencing the Broader WEEGE Landscape

Increased momentum around WEEG - reflected in resources such as the U.S. National Security Strategy, the Women Entrepreneurs Finance Initiative, and 2X Challenge - presents a greater opportunity for USAID staff to collect, analyze and apply WEEGE data. USAID staff can influence the WEEGE landscape by applying and sharing WEEGE MEL best practices. Disseminating proven approaches to developing MEL frameworks for WEEGE can drive synchronization and comparability not only across agencies (i.e., government, multilateral organizations, etc.) but also across countries, as well as between the public and private sectors, ultimately contributing to more effective programming and interventions. Conducting rigorous evaluationsOne method of conducting a rigorous evaluation is a randomized controlled trial. Careful consideration should be given before using this method, as it is not always a good fit for complex development interventions where control groups may be easily contaminated or difficult to find. - where strategic, relevant and ethically possible - can build the evidence base on what works (or does not work) to advance WEEGE.

To ensure successful WEEGE learning, USAID staff should do the following:

- Prioritize sharing evaluation findings, best practices and lessons learned to better harmonize with other stakeholders focused on WEEGE; work with others to learn from their experience

- Over time, contribute to identifying trends in WEEGE results at local, country, regional and global levels to better track WEEGE progress.

- Contribute to the broader evidence base on what works to improve and measure WEEGE development outcomes, drawing on MEL efforts and the integration of WEEGE across Development Objectives.

Drawing Upon Innovative Data Sources

Technological advancements have allowed for the use of big data that goes beyond household surveys or project evaluations, enabling new, big-picture understandings of WEEGE with faster turnaround and ability to analyze. Private sector data (such as financial institutions’ client-related data, or information on women-owned firms in global value chains) can also complement traditional survey tools. Drawing upon these sources can increase efficiency and reduce reliance on household surveys, which in turn lessens the time burden of data collection on the already time-poor and reduces the cost of implementing MEL frameworks.

Challenges and Solutions Related to WEEGE Data

In developing a strong WEEGE MEL approach, practitioners may encounter challenges stemming in part from the complex nature of empowerment itself, a concept that is “multi-dimensional, non-linear [and] reversible.”Karim, Nidal, et al. (2014), "Building capacity to measure long-term impact on women's empowerment: CARE's Women's Empowerment Impact Measurement Initiative," Gender & Development 22.2: 213–232. The complexity of WEEGE is reflected in the working definition outlined in Box 1. This is not an “official definition” of USAID or any other organization but rather a practical working definition that provides sufficient clarity in pursuing USAID’s economic goals with regard to gender equality and female empowerment.

Box 1: WEEGE Working DefinitionWomen’s Economic Empowerment and Gender Equality: Women’s economic empowerment exists when women can equitably participate in, contribute to, and benefit from economic opportunities as workers, consumers, entrepreneurs, and investors. This requires access to and control over assets and resources, as well as the capability and agency to manage the terms of their own labor and the benefits accrued. Women’s economic equality exists when all women and girls have the same opportunities as men and boys for education, economic participation, decision-making, and freedom from violence. This requires collectively addressing barriers to commercial activity and labor market participation, such as restrictive laws, policies, and cultural norms; infrastructure and technology challenges; unpaid care work; limits on collective action; and poorly enforced protections. Women’s economic equality is just one facet of gender equality more generally, which requires attention to the full range of gender gaps — economic, political, educational, social and otherwise. |

The working definition of WEEGE encompasses multiple dimensions that, for a given individual, may increase or decrease over time, such as access to and control over assets, or agency to manage economic opportunities.

WEEGE emphasizes the concept of power, understood as a woman’s ability to assert control over choices that impact her life. Within an economic context, this ability would include choices such as whether to seek higher education, gain employment or start or grow a business. From a measurement perspective, empowerment indicators reflect the extent to which women can make decisions freely and independently, without social pressure or coercion and without legal or social barriers curtailing their choices. Gender equality complements the concept of empowerment in emphasizing that individuals, regardless of gender, should have an equal opportunity to make economic choices that benefit them. Put another way, women should not have fewer or different economic choices or opportunities compared to men. From a measurement perspective, indicators that reflect gender gaps in employment or asset ownership, for example, demonstrate the degree of equal or unequal opportunities for men and women in the economy. The sections that follow will review some of the most prevalent challenges in measuring WEEGE and will introduce solutions to addressing these challenges.

Gender-Biased Data Systems

CHALLENGE: While sex disaggregation is now considered a best practice, it has not always been recognized. Many data sources are still not sex disaggregated nor reach the individual level, limiting the usefulness of existing data. Many current data sources and tools that focus on economic well-being have used the household as the smallest and primary unit of analysis and have not included sex disaggregation or individual-level indicators. Basic poverty data is based on household surveys, and household-level income is assumed to be divided evenly among adult members. This supposition runs contrary to evidence: it is widely noted that intrahousehold resource allocation is not always equitable and often disadvantages women.Lugo, Maria Ana and Dean Mitchell Joliffe. (2018). “Why the World Bank is adding new ways to measure poverty,” World Bank, https://blogs.worldbank.org/developmenttalk/why-world-bank-adding-new-ways-measure-poverty

Nevertheless, simple sex disaggregation and indicators that address gender are typically not included in measurement plans.UN Women (2018), Turning Promises into Action: Gender Equality in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. http://www.unwomen.org/-/media/headquarters/attachments/sections/library/publications/2018/sdg-report-gender-equality-in-the-2030- agenda-for-sustainable-development-2018-en.pdf?la=en&vs=4332. For example, studies show women lack equal access to financial services and present an untapped market opportunity.“Why Women’s Financial Inclusion Data Pays,” Data2X, https://data2x.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/WomensFinIncDataPays.pdf Banks, however, often do not disaggregate client data by sex, missing an opportunity to pinpoint gender gaps and ways to close them.

Similar gaps exist throughout the financial sector. Women-owned small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) constitute about one-third of all formal SMEs globally, yet there is a lack of comprehensive data on these firms’ characteristics, their constraints to growth and how to address those issues. (Refer to Box 2.) Sector-specific employment dataFor example, the mining industry occupation coding covers a full range of positions including supervisors, managers, professionals, technicians, plant operators and laborers while waste management sector occupation codes are limited to refuse workers, garbage and recycling collectors, refuse sorters, sweepers and related laborers. For further information see: https://www.ilo.org/public/english/bureau/stat/isco/docs/resol08.pdf is often limited and gender blind, preventing practitioners from identifying precise gender gaps and opportunities to increase women’s labor market participation, especially in male-dominated sectors.

Box 2: Sex-disaggregated Foreign Assistance Standard Indicators

|

SOLUTION: In developing and using MEL frameworks, as well as in designing and executing rigorous impact evaluations that can address these challenges, USAID staff should consider the following suggestions:

- While broader data systems are being improved, start by using what is already available. For example, Data2X and Open Data Watch offer a Ready to Measure series, highlighting sustainable development goal-related indicators for which data are currently collected at regular intervals across countries. Examples of these indicators (collected by the International Labor Organization and the Global Findex) include:

- proportion of young women who are idle (women aged 15 to 24 who are not employed, not in school, and not in training)

- females employed as a percentage of the working-age female population (aged 15 to 59), and female-to-male ratio

- proportion of employed who are self-employed workers, by sex of worker

- women’s share of non-agricultural wage employment

- percentage of adult women with a formal financial account, and female-to-male ratio

For additional resources, see Unit 1, Resource 1: WEEGE Data Sources, Unit 6, Resource 2: WEEGE MEL, and Unit 6, Tool 1: WEEGE Illustrative Indicators.

- Design MEL frameworks that challenge the notion that they must be gender - neutral (i.e., applied, measured, implemented and interpreted the same way for men and women). Start by asking which indicators can be disaggregated by sex and designed with gender in mind. By default, recommend that all relevant indicators be disaggregated by sex and age, at minimum.

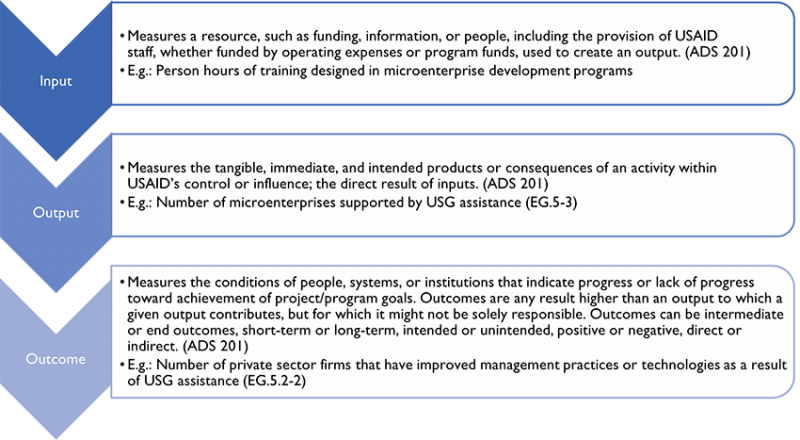

- Where possible, focus on WEEGE outcomes. Capture data not just on inputs and outputs but also on whether (and how many) individuals benefited from an activity or intervention (refer to Box 3). Prioritizing sex-disaggregated output and outcomes indicators will allow USAID to better capture its impact on women’s lives.

- When designing MEL systems, consider the level at which to measure outcomes (e.g., at the population level, or among a specific subset of women). Depending on the context of measurement, it may impact the types of tools or indicators needed to measure success.

- Partner with women’s groups to benefit from their knowledge and perspectives and build their capacity to collect data reflecting the realities of women and girls in their communities. Women from local communities are in a unique position to inform the design of programs and MEL frameworks, as well as to collect data that is accurate and relevant to their lives, especially when equipped with proper training and data collection tools. USAID staff should explore opportunities to forge partnerships with women who know their contexts best. Refer to Unit 3, Tool 1: WEEGE in Action - Engaging Women’s Organizations for additional guidance.

Box 3: Measuring and Tracking WEEGE Inputs, Outputs and Outcomes

Image

|

Complexity of Empowerment

To identify measurable empowerment indicators requires an understanding of social-behavioral research and studies of psychology. From a measurement perspective, empowerment indicators reflect the extent to which women can make decisions freely and independently, without social pressure or coercion and without legal or social barriers curtailing their choices. This section examines three measurement challenges regarding empowerment: qualitative vs. quantitative measures; measuring complex data at multiple levels (individual, household, community, national, global, etc.); and measuring a fluid (not fixed) condition. Each challenge is summarized and accompanied by suggested solutions and resources.

CHALLENGE: QUANTITATIVE VS. QUALITATIVE MEASURES: The concept of empowerment can be measured in both quantitative and qualitative terms as relates to assets and networks, labor market participation, decision-making, agency, leadership and self-confidence, among other criteria. Quantitative data resources are more plentiful, but often they are not disaggregated by sex, age, income level or other characteristics. Sex disaggregation of empowerment data is driven by the source, researcher, implementer, and sector, but few evaluators have systematically disaggregated results by sex. A lack of sex-disaggregated data obscures inequalities that exist among women and men.

Measuring the qualitative dimensions of empowerment is more challenging. WEEGE practitioners continue to face difficulties devising survey instruments to capture individuals’ mindsets, because qualitative data is often story-based and not quantifiable. It is often more difficult to collect and summarize, as it requires interpretation and processing. Nevertheless, qualitative data provides important context and depth to better understand quantitative data. For more information on different types of indicators and definitions of quantitative and qualitative indicators, refer to USAID’s Monitoring Toolkit: Selecting Performance Indicators and Tool 1: WEEGE Illustrative Indicators.

SOLUTION: Suggestions for programs and activities to measure and evaluate quantitative and qualitative dimensions of empowerment include the following:

- Develop a theory of change (ToC), sometimes referred to as a development hypothesis, for the strategy, project or activity. The ToC can prioritize identifying aspects of empowerment that the strategy, project or activity plausibly can impact, pointing to specific indicators that can capture change.

- Disaggregate individual-level indicators by sex and other relevant factors (such as, age, marital status and income level).

- Utilize both qualitative and quantitative measurement tools (Resource 2: WEEGE Monitoring, Evaluation and Learning for a list of potential resources). Link qualitative research methods to the ToC, suggesting related indicators in each context, and ensure measurement of relevant factors through quantitative tools such as surveys. Conduct fieldwork using non-survey instruments to shed light on the dynamics, constraints and opportunities within a given context. These include focus group discussions, vignettes, and role plays, which reduce the risk of social-desirability bias (that is, a survey respondent giving what they perceive to be the acceptable answer). Non-survey instruments reveal attitudes that people themselves may not be aware of and provide an important supplement to quantitative findings. Findings from qualitative studies also can inform researchers’ priorities and the design or fine-tuning of quantitative survey instruments.

CHALLENGE: MEASURING EMPOWERMENT AT MULTIPLE LEVELS: Empowerment relies on a complex interplay of changes in an individual’s “own aspirations and capabilities (agency), the power relations through which she must negotiate her path (relations), and the environment that surrounds and conditions her choices (structure).”Karim, Nidal, et al, 2014. To obtain a clear picture of empowerment, therefore, MEL systems must collect, analyze and use data sources from the individual, household, sub-national, national, regional and global levels.

SOLUTION: Recommendations for effectively measuring and collecting this information at all levels are as follows:

- Prioritize sex disaggregation and broader gender data within MEL frameworks, from the design of the ToC through all aspects of the intervention. Consider the broader dynamics (such as a woman’s engagement with her household or community, as she receives training or gains access to new assets). Failing to do so will jeopardize any long-term benefits to women, and may even adversely affect women due to shifts in intra-household and community dynamics.

- Incorporate process-oriented measures that reflect whether activity design and implementation are inclusive, consultative and rooted in the local context. Include indicators that reflect the degree to which local women and women’s groups participate in designing strategies, projects, activities and evaluations. This can ensure that interventions consider broader dynamics within a specific context.

CHALLENGE: MEASURING A FLUID CONDITION: Empowerment is a process and an ultimate outcome—not a fixed condition that can be fully achieved and never diminished. Strong evidence indicates that empowerment gains can dissipate or increase over time, as a given intervention interacts with other dimensions of women’s lives. Women’s lives are complex and multifaceted; for example, the benefits of receiving a cash transfer, loan or in-kind asset can be counteracted by other factors, such as control of income or bank accounts by their husbands or other household members.Jakiela, Pamela, and Owen Ozier, “Does Africa need a rotten kin theorem? Experimental evidence from village economies,” The Review of Economic Studies 83.1 (2015): 231–268.

SOLUTION: To capture these complexities in MEL frameworks without losing focus, consider the following suggestions:

- Pinpoint anticipated targets and outcomes in addition to inputs and outputs, to help make a ToC more concrete and actionable.As a resource on how to identify and distinguish between WEEGE direct, intermediate, and final outcomes, see Buvinic, Mayra and Megan O’Donnell, “Revisiting What Works: Gender, Economic Empowerment, and Smart Design,” Center for Global Development (2016)

- Wherever possible and strategic for USAID programming, build in budget and time for impact evaluations or follow-up surveys that reflect whether initial impacts are sustained and whether interventions are transformative.

- Consider not only the benefits that an intervention can bring about, but also the potential harm it could generate. Include measures that capture whether efforts to mitigate against risks are effectively implemented.

Harmonization Versus Customization

CHALLENGE: USAID staff may encounter tensions between two priorities: agency, government or global efforts to harmonize or standardize measures for WEEGE on the one hand, and the need for local, context-driven interventions that address WEEGE barriers relevant to that context on the other. Given that dimensions of empowerment and equality are embedded in sociocultural norms and systems and communities with their own beliefs and values, localization of measurements may make it more difficult to harmonize and standardize measures for WEEGE across countries. Constraints on women’s economic empowerment may vary in different cultural contexts. In some contexts, constraints on women’s economic empowerment will manifest in limitations imposed on their mobility, keeping them at or close to home. In other contexts, women’s physical mobility may not be constrained, but they may face limitations on their independent decision-making and choices related to health care, contraception, or savings and investment.

SOLUTION: Questions and indicators should be nuanced for different contexts and interventions (for example, a motorbike as an asset, might be considered a meaningful mode of transportation in one instance, and in another situation, it can serve as collateral for a loan). See Resource 2: WEEGE Monitoring, Evaluation and Learning for documents that provide guidance for collecting context-specific data on women’s empowerment.

Conclusion

A robust MEL agenda is critical in driving progress for WEEGE. Though MEL planning is at times considered a secondary priority relative to program implementation, it is essential to ensure intended impact and to mitigate potential harm. Prioritizing MEL in the development of country and regional strategies, as well as in projects and activities, is pivotal in informing USAID staff and partners what aspects of program design are most likely to drive impact. In turn, robust monitoring and evaluation frameworks and the incorporation of a strong learning agenda can ensure that future strategies and projects incorporate proven approaches to improve women’s economic opportunities and outcomes. By integrating MEL components across all levels of strategy, project and activity development and execution, USAID staff can ensure that interventions are evidence-based, effective and sustainable.