USAID Official

COVID-19 and the Economic Outlook for Development in the Global South

Image

This was originally posted on the USAID Policy Medium blog and was authored by Peter Richards, Senior Economist, USAID’s Bureau for Policy, Planning and Learning.

The economic impacts associated with the emergence and global transmission of COVID-19 on East Asia, and more recently, Europe and North America, have caught the attention of the world. The unprecedented reduction in global demand for energy, material and other resources that have followed, however, will have significant implications for the global south. Most poignantly, the recent collapse in prices for many key commodities suggests that trouble lies ahead for many developing countries.

Economies across the global south, particularly Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa, tend to be reliant on demand for natural resources and other basic commodities. In many of these countries, commodity export, in most cases, comprises more than 80 percent of total merchandise exports in these regions. For most of this century, amidst the booming demand for food, fuel, and manufactured goods, commodity exports were a good bet. High commodity prices brought new capital inflows into developing countries. As prices for exported commodities rose, they filled coffers, drew in investments to expand capacity and created new employment opportunities.

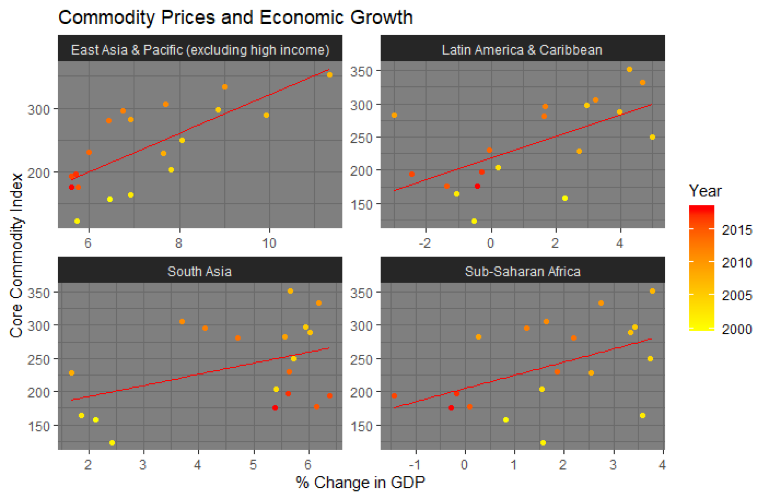

At a regional level, general commodity indices such as the Thomson-Reuters Core Commodity (TRCC) Index, a weighted composite of 19 fuel, food, mineral, and material commodities, have been good predictors of economic growth. Since 2000, the TRCC explains 20 percent and 37 percent of GDP growth in Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa, respectively.

The economic effects of COVID-19 on the Global South may not be as immediately visible as the now-stalling service and manufacturing sectors are in America, Europe, and East Asia. However, the decrease in demand for the commodities that power these stalled sectors is poised to shake the economic foundation of much of the developing world.

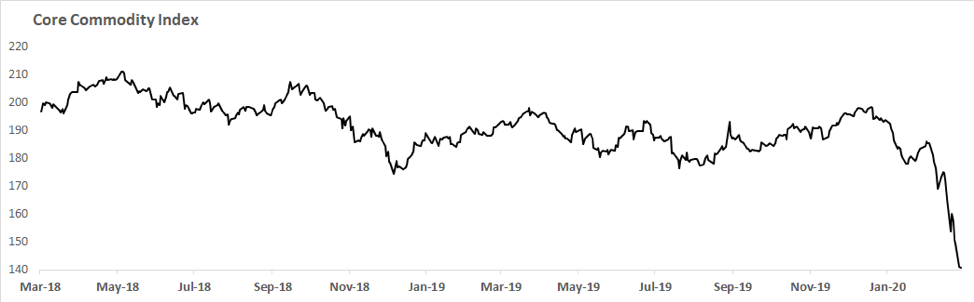

Prices for core commodities have been declining since the beginning of 2020. As COVID-19 developed into a global health issue, core commodity prices decreased substantially. Since March 5th, the TRCC index has fallen by ¼, from $165 to $120. This is less than half of the index’s average value during the last twenty years.

In Latin America, each 1 dollar drop in the TRCC commodity index predicts slightly more than a .023 percent decline in economic growth (change in GDP). For East Asia, South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa, it predicts a decline of 0.018, 0.01, and 0.011 percent, respectively. Put into these terms, the roughly 50 dollar drop in the TRCC index observed over the past two months translates to a 0.5–1 percent reduction in economic production. Unlike in 2009, when a similar drop occurred when prices were at record highs, today’s drop in commodity prices is occurring at a time when prices are already low, when supplies and stocks are high, and when many economies across Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa are already struggling.

For much of the 2000s, the developing world enjoyed a long, upward trend in commodity prices, largely driven by growing global demand and a rapid increase in the global capacity for organizing and executing cross-border trade. Not surprisingly, it was an era of strong economic growth and fast-falling poverty rates. That era may well be over.

In theory, commodity prices may well return to the high prices of the past decade. The current rift between OPEC and Russia may well be resolved in the coming months, potentially driving fuel prices higher. Alternatively, consumption could quickly return to, or even exceed, pre-COVID-19 levels, as globally, consumers rush to satisfy a pent up wave in demand. However, it is equally possible that low commodity prices, the norm of much of the late 20th century, will be here to stay. If so, developing countries, and the development community, will need to think strategically about how to diversify their economies and identify new opportunities for growth.

USAID is well-positioned to engage in a post-COVID-19 economic landscape. Earlier this month, Congress appropriated $1.25 billion in supplemental funds for the Department of State and USAID to address COVID-19, including $250 million in Economic Support Funds to address second-order impacts, through the Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act. These funds are not only critical for assisting the global response to COVID-19; they will provide the financial ammunition that USAID will need to address the economic, security and stabilization challenges which are likely to follow in the disease’s wake.

The Bureau for Policy, Planning & Learning shapes USAID’s global development policy & program guidance and engages in partner development cooperation.