What is (and isn’t yet) Impact Investing?

Image

To continue developing a deeper understanding of impact investing and finance for development, Autumn Gorman from USAID's Private Sector Engagement Hub discusses what is and what is not yet impact investing in this first installment of a four-part blog series. Access the series' second, third, and fourth installments.

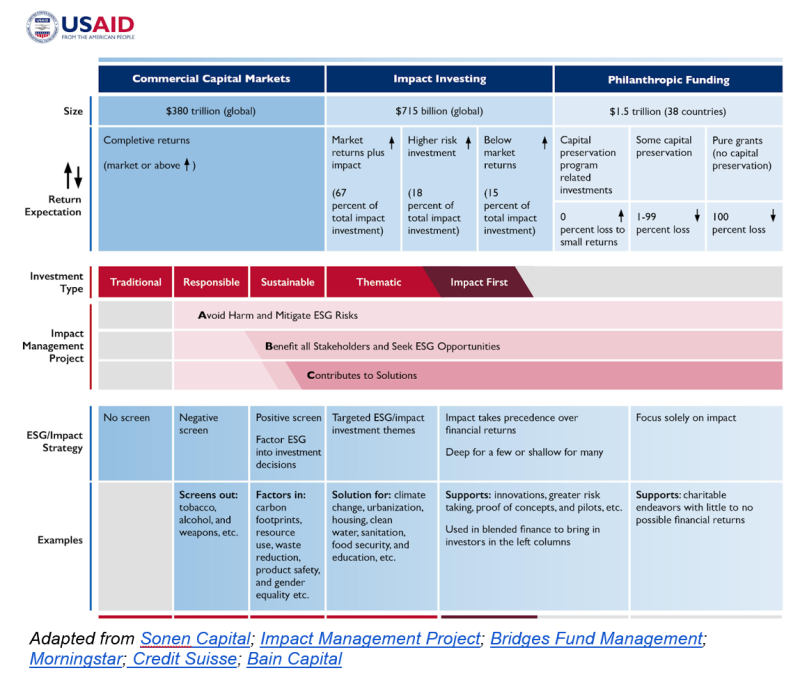

As many of you know, impact investing isn’t one thing. It is more of a spectrum, as indicated in the graphic below. The Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN) defines it as “investments made with the intention to generate positive, measurable social and environmental impact alongside a financial return.” Sometimes, that return might be negative, and I have included philanthropy in the chart to show the sub spectrum of negative return that we typically call funding. There is growing interest among parties across the entire spectrum to find ways to blend different pools of capital to achieve development goals.

Capital Available and Impact Potential

Image

We know that 90 percent of capital flows to developing economies come from private sources, far outpacing traditional development assistance flows, and there are vast pools of local currency capital in USAID partner countries. A vast majority of global financial assets, approximately $380 trillion, is purely commercially-oriented – seeking financial returns with no consideration of environmental or social returns. Philanthropic foundation assets exceed $1.5 trillion among 260,000 independent foundations, corporate foundations, government-linked foundations, and family foundations, according to the Global Philanthropy Report (which covers 38 countries). The good news is that GIIN estimates the global impact investing market - seeking environmental and/or social returns - includes 1,720 organizations with $715 billion in assets under management (AUM) at the end of 2019! And that amount is growing rapidly, at a rate of 30-50 percent per annum. While a small slice of the overall capital pool, it is still a huge amount of funds.

Although the lines blur (commercial entities may manage foundations’ assets), that commercial capital pool is starting to pay more attention to environmental and social issues in one of two ways.

The first is through negative screening, or what Sonen Capital and others have called “responsible investing”, where a company would exclude investments based on certain social, environmental, or governance criteria. An example is mutual funds that won’t hold stock in tobacco companies to meet the expressed desires of needs of their shareholders. The second is through positive screening, or what Sonen Capital and others have called “sustainable investing.” It is about identifying, mitigating or avoiding risks related to environmental, social and governance (ESG) issues for individual companies (Note: ESG investing is more about how these factors affect the company, not the company’s effects on the world). For example, an ESG investor looking at Coca-Cola’s growth prospects in the Middle East might consider the risks of water scarcity and changing policy into how it assesses the risks of that investment. The Forum for Sustainable and Responsible Investment estimates that at the end of 2019, there were $17.1 trillion in sustainable investing assets in the United States alone, growing 42 percent since 2012. According to Morningstar, 72 percent of U.S. investors have expressed interest in sustainable investing, so the growth is likely to continue.

However, sustainable, or ESG investing is not yet true impact investing because they aren’t yet (collectively) moving into what the Impact Management Project calls “Contributing to Solutions,” such as investing in new solar farms in emerging markets to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Unfortunately, however, there is also growing confusion and controversy around ESG and impact investing that results in claims of “greenwashing” or “impact washing” with assets branded as sustainable or ESG. For example, with the war in Ukraine, some weapons companies are now considered a sustainable investing asset with social outcomes, although such companies have historically been screened out as part of responsible investing (a lower step on the spectrum of impact). Since environmental and social standards and auditors do not yet exist as they do with financial reporting, it is challenging for investors to know whether a company’s classification of an investment as “sustainable investing” can be trusted. But the demand is growing for such standards, and the European Union and the Securities and Exchange Commission in the United States are starting to respond.

Regardless of how an investment is classified, there is space for the development community to think bigger: to engage larger pools of capital in ways that may have broader, but shallower impact, in addition to the more typical smaller pools of capital that have deeper, but narrower impact. In other words, this means employing the same kind of portfolio approach that investors themselves use to take advantage of this growing demand. What might that look like?

Investing Strategies: Balancing Risks and Returns

Investors invest for different reasons and purposes. Pension funds look towards lower-risk investments with longer tenors to match their future obligations to retirees. Venture capitalists take a higher-risk for higher-return approach in their portfolios, and actually expect to lose all of their money on several investments with the expectation that one of them will be a “unicorn” (a startup company worth $1 billion or more) in a relatively short period of time.

Impact investors seek environmental and/or social returns (or impact) in addition to financial returns. Sustainable investors, also called ESG investors, consider environmental, social and governance factors when making investment decisions but financial returns remain the focus. Each seeks risk-adjusted returns, which means the return must be proportional to the risks of the investment, but what makes them fundamentally different is how they define risks that are material (or relevant) to the investment, and the desired rate of return. The worlds of impact investing and ESG investing are starting to come together in interesting ways, but they remain quite distinct due to how they view risks (both perceived and actual) and desired return.

Scaling Impact Investing to Accelerate Development Progress

What I find particularly interesting is the amount of capital on the far left of the chart moving towards the right, albeit in relatively tiny steps Commercial Investors are moving into ESG because those risks are starting to factor into how they calculate risk-adjusted returns. But they aren’t (yet) true impact investors – at least in the way the development community would prefer, so how can we nudge them and bridge the gap towards impact at scale in emerging economies? For anyone who has taken the Mobilizing Finance for Development course or has worked in this space, you know there are some critical challenges. We work in environments and sectors that come with outsized risks. Financial needs don’t often match what providers can offer–for many good reasons, including ticket size. It is very difficult to invest $1 billion into SMEs that only need $250,000. Each investment requires time and effort. It would simply take too long to make 4,000 separate investments.

But there are things we can do to help better match demand and supply, and to support commercial market actors to move towards greater impact by supporting greater transparency and helping investors bridge the ESG <> impact gap.

To get a better sense of how to do this – as a small investor or a big investor, or as a small company or a large one – check out the Impact Management Project and the (free) Coursera course Cathy Clark and the CASE Team developed on Impact Measurement & Management for the SDGs.

To better understand how to segment markets in ways that align with finance providers, check out Songbae Lee’s finance series on Agrilinks.