In search of more equitable impact: what are effective strategies for achieving more holistic WEE outcomes in market systems development (MSD) programmes?

Image

New research from World Vision Australia (WVA) highlights ways their Women’s Economic Empowerment (WEE) approach realized women’s access and agency outcomes and social norm change.

Holly Lard Krueger, Managing Partner and Inclusion+ Practice Lead at the Canopy Lab spoke with Ellie Wong, Economic Empowerment Manager at WVA, about the findings and five practical strategies to realise holistic WEE outcomes. This exchange is part of a new blog series from the Canopy Lab and part of their larger Inclusion & Leadership Research Initiative.

1) Measurable progress towards WEE starts with a common vision of success.

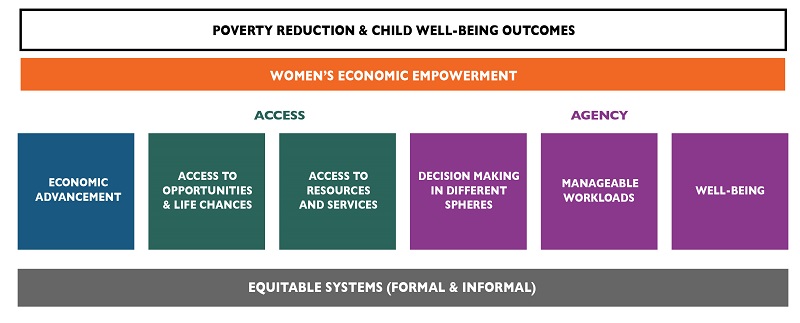

According to Ellie, a Women’s Economic Empowerment (WEE) expert, the journey toward achieving more equitable impact starts with defining a common vision of success. Or more concretely with answering a key question: “what does it mean for [an organization/program] to economically empower women?”. With the goal of developing WVA’s common vision for WEE, applicable across their economic empowerment program portfolio, Ellie and her team worked with WEE and MSD experts, Samira Saif, Linda Jones and Sumera Jabeen, to articulate a theory of change (ToC) (Fig. 1), WEE Framework, technical guidance[1] and WEE Indicators and Tools.

WVA’s WEE framework builds on the foundational Women’s Empowerment and Markets Systems (WEAMS Framework) resource, and other literature, which were contextualized to the goals and values of World Vision i.e. poverty reduction and child-wellbeing. In addition to the WEAMS Framework’s economic advancement, access, and agency domains, World Vision Framework’s added a domain on equitable systems, including social norms.

Figure 1: WVA Theory of Change

From World Vision’s lessons and other literature, addressing social norms is key to the sustainability of economic empowerment. outcomes, because if women’s families, communities, and market actors more broadly are not supportive of WEE, there are risks that the changes promoted by programs will not ‘stick’. According to Ellie, a holistic vision of success has been critical to encouraging the programming pathways to achieve this.

WVA’s Standardized WEE indicators:

- Economic advancement: % households with increased income (male headed vs. female headed)

- Access: % women and men adopting recommended business management practices

- Agency:

- Decision making: % households with equitable decision making in productive/domestic spheres

- Manageable workloads: Average # hours per day spent on leisure and sleep

- Well-being: - Average well-being score

- Equitable systems: % women and men with supportive attitudes towards women's economic participation.

In the Australian NGO Cooperation Program (ANCP) funded MORINGA Indonesia program, Ellie observed how the introduction of the WEE framework translated into new and tangible actions by the team. For example, working in six agricultural value chains, the program had initially paid less attention to agency. The framework and specific indicators were key to helping the program to identify and respond to this gap, by piloting activities that could tangibly contribute to women’s decision making linked to household budgets (including investment opportunities linked to the business model promoted), manageable workloads, and well-being.

The program and WVA collaborated on a Gender Inclusive Financial Literacy Training (GIFT)[2] pilot targeting couples, which was scaled over time across three provinces. The program partnered with credit unions who have started to see gender as a key part of their brand and customer outreach strategy. In addition, the program partnered with religious leaders as allies for gender equality, given the alignment with their own work in pre-marital counselling where conflict over finances is common. GIFT is now being adapted and implemented by World Vision in eight other countries as a promising practice.

2) Creating consensus around a common set of indicators enables comparisons across the WEE effectiveness across programs, and fosters a learning culture.

Considering the breadth and diversity of WVA programs, creating consensus around a common set of indicators to measure WEE across the portfolio was initially challenging but it has enabled WVA to draw out important insights into how to best achieve holistic WEE outcomes. These are being used to improve current programs as well as to inform future program design.

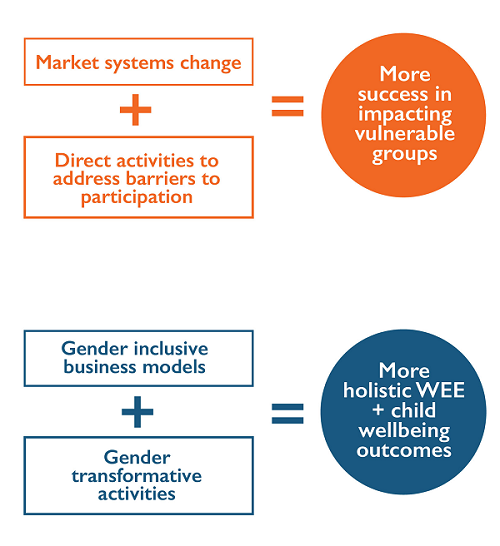

An ANCP funded Meta-Review of WVA’s Economic Empowerment portfolio of 11 projects valued at over USD 46 million revealed that projects with a WEE twin-track design were more likely to achieve greater impact on WEE (Fig. 3). These projects incorporated both gender mainstreaming (gender inclusive business models) and targeted components (gender transformative approaches such as GIFT, Equimondo’s Mencare and World Vision’s C-Change models) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: World Vision’s Hypothesis of Change: inclusive Market Systems Development & Women’s Economic Empowerment.

Specifically, projects with a WEE twin-track design were more likely to result in improvements across domains, including:

- Higher proportion of women participants benefiting from improved incomes and access to new opportunities and resources (economic advancement, access);

- Improved decision making in the productive and domestic spheres (agency/decision making);

- Increased satisfaction about time use (agency/manageable workloads); and

- Improvements in attitudes towards women’s economic participation (equitable systems).

Similarly, the study found that gender transformative activities promoting equitable alternatives through participatory sessions involving questioning of attitudes, critical reflection, and dialogue with households, over time, were key in promoting agency and equitable systems.

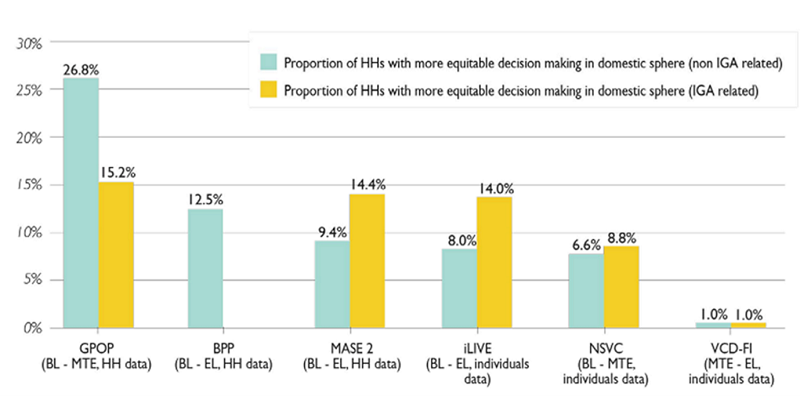

Figure 3: Baseline (BL), mid-term evaluation (MTE), endline (EL) percentage point change in women’s decision making in domestic and productive spheres of programs with a WEE twin-track design and gender transformative approach (GPOP, MASE 2, iLIVE, NSVC) vs programs with no intentional focus on gender inclusion/WEE (VCD-FI).

3) Commercial incentives AND social norms drive behavior change in market systems: we need approaches that work at both levels.

The importance of commercial incentives for the design of effective interventions on MSD programs is clear, and reinforced through tools such as who does?, who pays?. From Ellie’s perspective, program seeking equitable impact need to also understand how social norms drive behavior.

“Our WEE approach, consistent with our approach to inclusive Market Systems Development, works at two levels. We work with market actors to introduce more inclusive business models and unlock economic opportunities and market access, AND we work with households and communities to address restrictive social norms and address unequal gender relations. Both are linked to core MSD principles around addressing underlying root causes of market dysfunction and promoting sustainability. If women are not realising their potential in value chains, we have an underperforming system. Addressing social norms is about shifting the informal rules of a market system so that women have a positive enabling environment. If a woman’s community and family are not supportive of her new income generation activity, WEE outcomes will not be sustainable.”

For example, the Nutrition Sensitive Value Chains for Smallholder farmers (NSVC) program worked on a business model centred on the distribution of improved agri-inputs to improve incomes and productivity in Jamalpur, Bangladesh. Despite initial reluctance from the private sector, the program made the business case that women are not only good customers of agri-inputs but effective intermediate service providers – or Community Sales Agents. Given the initial analysis of the significant barriers and social norms held for women, a multi-pronged approach was developed to address norms and unequal gender relations at multiple levels – amongst households, producer groups and communities. This has been achieved through the Mencare model[3] and GIFT training for couples, folk songs and engaging religious leaders as allies for WEE. Interestingly, the Mencare model has been expanded to religious leaders, private and public actors, with a key learning on the importance of getting partners engaged from the beginning.

The Meta-Review validated the hypothesis that World Vision’s WEE approach and dual focus on systems, as well as households and communities, accelerates inclusion outcomes. Ellie sees that some of WVA’s biggest successes have come from pilot programs that think outside the proverbial ‘donut’ and identified key influencers within a community to address restrictive social norms.

4) Specificity is important when it comes to shifting (and measuring changes in) social norms.

Many MSD programs focus on women’s access, and work on social norms indirectly. They operate under an assumption that by improving access, it may be possible to improve status and agency. Ellie knows that access can contribute to agency. However, in many contexts where harmful norms are a key challenge, she believes that programs might be missing the opportunity to realise holistic WEE outcomes, inclusive and sustainable growth AND systemic change by not leveraging both indirect and direct strategies to tackle social norms. “If in the international development and gender equality space, we have good evidence of the effectiveness of gender transformative approaches in addressing social norms, why wouldn’t we use every tool in our toolbox to make sure our economic empowerment outcomes are sustainable over time?”.

One of the reasons why social norm change is challenging is the fact that it is highly context specific, and it can sound unachievable to program teams who (understandably) want to set achievable program targets. One- off, cookie cutter approaches do not work and could even cause harm. According to Ellie, WVA programs that have been successful in shifting social norms have spent time on assessing the context and identifying the social incentives for gender equality amongst households and communities. In addition, programs have prioritised specific norm changes such as elevating women’s voice in household budgeting (Fig. 4). This is a departure from trying to achieve important, yet vague and difficult to measure, goals around increasing women’s voice.

Having more concrete social norm change goals, and practical activities like GIFT and Mencare that include reflective sessions for couples on including women’s voices in the family vision, budget goals, and sharing the care work, helps to demystify the topic of agency for staff. She noted that, “Once we show teams the indicator tool on community attitudes to women’s economic participation, they see that their activities like the 24-hour clock can reasonably shift attitudes from ‘Men should determine how women/their wives spend their time’ to ‘Women and men should jointly discuss workloads for the business and care work’ over time”.

Figure 4: IEC materials targeting women’s agency linked to the household budget accompany gender transformative Mencare and GIFT activities in NSVC and GPOP projects in Bangladesh.

5) Intentionality is at the heart of achieving more equitable impact.

According to Ellie, having a clear design process which identifies, defines and prioritises specific target groups from the outset is obvious. Yet, it is unfortunately often overlooked thus undermining a program’s ability to achieve more (equitable) impact – whether this is about reaching poorer farmers, women, youth, or persons with a disability. Using World Vision’s WEE Framework, this means understanding problems and opportunities that women experience compared to men in relation to economic advancement, access, agency, and equitable systems. This needs to inform the design and tools of early-stage research and market analysis.

When making design decisions, a clear prioritisation framework is key. We need answers to key questions at the beginning: To what extent are we going to focus on value chains and business models where women can benefit? Are we going to invest in intervention pathways to directly address agency and social norms? Trade-offs are likely – given women are often concentrated in the least profitable value chains. “Equitable impact is about strong design-thinking and the management response to reflect this in your ‘big rocks’ - the team, partners, interventions and budgets.”

Gender and market systems training at the start can ensure there is a common vision of equitable impact, and the multi-disciplinary skillset to implement, monitor, and pivot. Ellie says key for World Vision has been equipping teams to use a gender lens as another analytical skillset to better understand market systems and work towards a common vision of economic empowerment.

[1] Please see World Vision’s WEE video including how the approach is being implemented in the Nutrition Sensitive Value Chains for Smallholder farmers (NSVC) project in Bangladesh, NSVC evidence brief, and the shorter WEE technical implementation note for field teams. Find out more about WEE case studies in iLIVE Sri Lanka and MASE 2 Cambodia program evidence briefs.

[2] Please see World Vision’s GIFT video on the implementation in the ANCP MORINGA Indonesia program, evidence brief and the shorter technical note for field teams to adapt and implement the GIFT curriculum in other countries.

[3] Developed by Equimundo, this is a gender transformative model to train couples over a 12-14 week period on issues of gender equality. Program P has been adapted and/ or implemented in at least 18 countries around the world. Results from a randomised controlled trial of Program P in Rwanda released in 2018 reveal powerful impacts on health and violence outcomes.