The Puzzle of Assessing System Change: Three Lessons Learned as Evaluators—Part 1

Image

If you’ve ever tried to evaluate the extent of system change, you know it’s a fascinating—but tricky—process.

We had this opportunity with the Feed the Future Harvest II program in Cambodia. Harvest II operated from 2017–2022 with a budget of $21.2 million. It aimed to increase sustainable economic opportunities in the horticulture sector in Cambodia. The program implemented a myriad of interventions with firms, their supplying farms, associations, and government agencies. We were contracted to evaluate what systemic changes Harvest II made progress on by the end of the program, focusing on four horticultural subsectors. (Check out the full findings report here).

Looking back on the evaluation, it was indeed a fascinating—but tricky—process.

In this three-part blog series, we share lessons on the evaluation process with brief examples. For each lesson, we reflect on what worked well and what didn’t in the evaluation process. The lessons are:

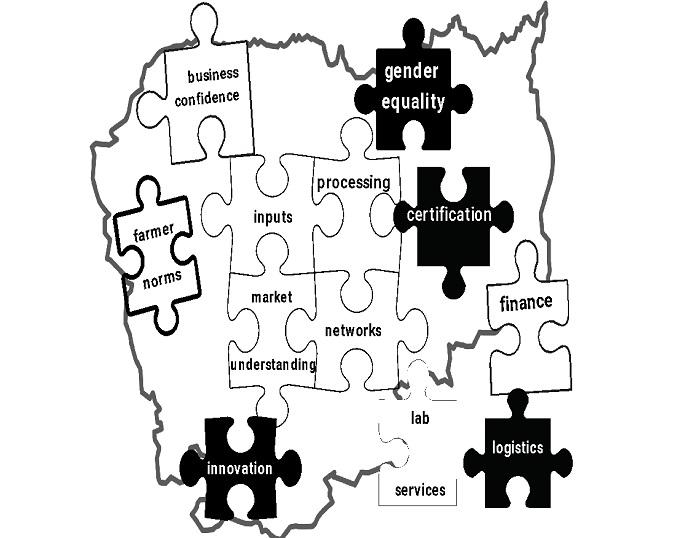

- Evaluate how the ‘puzzle pieces’ of the system are or are not fitting together.

- Recognize that a big contribution to a small system change may be more important than a small contribution to a big system change. (Blog 2)

- Start from the program strategy and system context to determine which dimensions of system change to evaluate. (Blog 3)

In this blog, we discuss lesson 1 learned in the evaluation process.

Lesson 1: Evaluate how the puzzle pieces (e.g., the various elements or factors influencing change) of the system are or are not fitting together.

Image

Many system change cases have focused on how an individual innovation has diffused through a market system and influenced other aspects of it—think terms like ‘crowding in’ and ‘response.

Yet the evaluation of system change in the horticulture sector in Cambodia was more like a puzzle.

- How were the different pieces of the system fitting together and reinforcing each other?

- Were there missing pieces, constraining otherwise promising improvements?

The pieces we considered were diverse: steps in the value chain, supporting functions, norms, links, innovation, processing, regulations, infrastructure, business confidence, and more. During the evaluation, it became increasingly clear that more puzzle pieces in place made it easier for more to be added and for system change to accelerate. But, when many pieces—or key pieces—were missing, the process was slower and harder, even though the pieces already in place were no less essential. It really did feel like a physical puzzle!

|

Example: The USAID Feed the Future Horticulture Innovation Lab program that ran from 2009–2014 introduced nethouses for vegetable production—simple structures made of a frame with netting over the top. Nethouses help farmers to control the environment better, enabling them to lower the use of chemical inputs, increase yields, and increase quality. However, adoption among farmers was slow initially because other key puzzle pieces in the vegetable system were missing. Although nethouses were introduced before 2019, adoption didn’t significantly speed up until urban, premium market demand for local ‘safe’ vegetables increased, and supply chains into urban areas improved. The COVID-19 pandemic boosted this trend by reducing competition from imported vegetables and expanding the online sales delivery network. By the end of the program, increased demand, stronger supply chains, improved delivery networks, better information flows, and farmers’ use of nethouses were working together to drive growth and innovation in the premium segment of the vegetable market system. |

Reflections:

- It was important to get as clear a picture as possible about what puzzle pieces were essential to the program’s future vision for a well-functioning market system. Identifying pieces relied on a combination of value chain analysis, considering system dimensions from literature, probing the program team’s vision for change, and listening to market actors.

- Using the Pragmatic Approach to Assessing System Change, we found asking questions from a ‘helicopter’ perspective was useful to understand how the puzzle pieces of a system were or were not working together. We started our interviews with general ‘overview’ questions, such as: “What has changed in the vegetable sector over the last five years? How? Why?” Respondents typically answered by naming a number of puzzle pieces that had recently been put into place, such as certification, or that were noticeably missing, for example, lab services. We could then probe how the new or missing pieces were affecting other pieces.

-

We found that it’s not always possible to judge with confidence which recent innovations may have a big impact in the future. The nethouses did not have a widespread impact when they were introduced more than a decade ago, but now this technology is one of the most influential in enabling farmers to meet growing urban, premium market demand. Identifying the puzzle pieces that were important to the program’s vision enabled us to consider the potential future influence of innovations that might not be making a widespread impact yet. It was also worth looking back further than the timeframe of an individual program for the factors that helped to put key puzzle pieces in place. (For more on this, see Adaptive Management Across Program Cycles: Look into Coherence in Time.)

Authors:

Alexandra Miehlbradt, Makararavy Ty, and Lara Goldmark