Pushing for Structural Changes Over Short-Term Changes in Behavior in Market Systems

This post was written by Luca Crudeli and Dun Grover, ACDI/VOCA was originally published on Vikāra Institute's website.

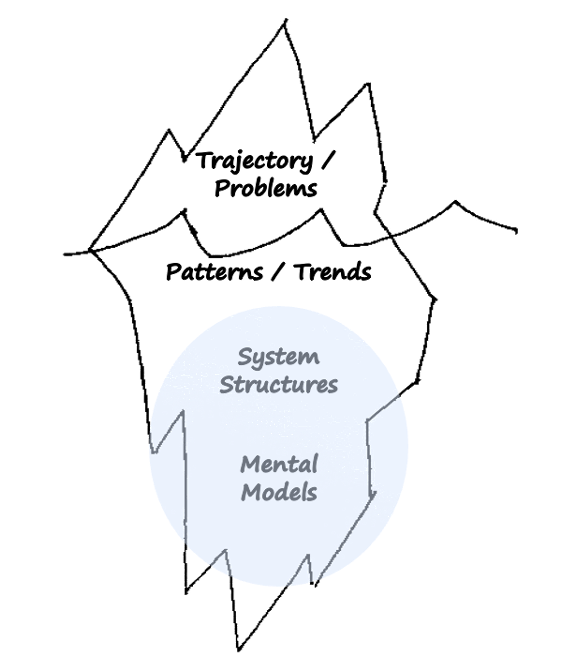

The blog does a great job of highlighting the challenges of actually taking a systems-thinking approach. Often projects, practitioners, donors, etc., look superficially at a market system or society and observe patterns/outcomes that do not align with their mental models or preconceived ideas, so they assume something is broken. However, as the blog points out in stark terms, complex social systems have evolved to operate the way they do because there was/is something attractive/useful to that society. For example, recent MSR research highlights that how communities manage risks can be highly dependent on local informal social norms that may not be readily observable. At the same time, the way they manage their crops or animals might be, so we focus on changing those easily observable behaviors in crop management/animal husbandry. MSR research suggests that we might not recognize that we are asking/encouraging them to make a trade-off between informal social safety net mechanisms that they rely on to manage risks and improved commercial farm management as we define it. As the blog points out, real systemic change only happens internally to a system as many forces and factors adapt, creating some disruption and allowing for new behaviors/network connections to emerge. System actors, based on their context, will determine if the new behavior/relationships are attractive (better than what they are doing) enough to change or not. While highly simplified, this idea that change is context-dependent, messy, takes steps forward/backward/sideways, requires an ability to zoom in and zoom out, and must be understood over time is critical. Still, it often makes current ways of assessing attribution to project performance unhelpful. As the authors deftly point out, embracing the messiness of systemic change is not easy but quite essential to moving MSD and MSR forward.

Image

The last Market Systems Symposium we attended in person was in 2019. We remember that event because the things we have learned at the Symposium and a subsequent blog by Marcus Jenal spurred a fundamental internal discussion (which we also turned into a blog that was subsequently reposted by Marcus) on the relationship between behavioral change and market systems change. At the time of the workshop, our leading market systems development (MSD) activity in Honduras, the USAID Transforming Market Systems (TMS) Activity, was turning one year old and had just completed its inception diagnostics.

The main point of the debate in 2019 was that MSD projects are often too focused on behavioral change to be able to look at the wider changes needed in the system as a whole. This bias often results from a neoliberal, paternalistic attitude, in which project teams think their purpose is to show market actors the “right” way of behaving. Once market actors embrace these behaviors, and such behaviors are brought to scale, everything will improve by amplifying the "better behavior." This progression follows a linear growth logic to a "tipping point," where the good behavior becomes the norm.

Image

Fig. 1 - "Good" behaviors are not easily replicable

The first problem with this approach is that it is impossible to define what “'better behavior” looks like in complex systems, since it is impossible to predict the outcomes of such a behavior. The second point, made by Marcus, is that to aim for specific system changes, we cannot focus on behavior alone but also must consider the environment in which those behaviors exist. The environment (or system) determines whether the behaviors we are introducing will lead to successful outcomes and be worth replicating. A corollary to the importance of the environment is that it may not always conform to our Western normative views of how the world should work. However, it can still produce inclusive outcomes that spur innovation and growth.

If we can summarize the discussion we had in 2019, we can say that if you give a person a fish, you will feed them for a day. If you teach them how to fish, you will feed them until the fish in the ocean run out. But suppose instead you strengthen the system's capacity to provide evidence and produce innovative and adaptive ideas. Then you improve the environment that shapes the person’s decision-making process. In that case, you will have improved their resilience. The person will be better able to decide whether to continue fishing or do something different and continue to adapt to changing conditions. The downside, in terms of our expectations for MSD projects, is our ability to attribute the change in material improvements in the person’s life to the changes they will embrace on their own, as opposed to what behaviors we “made happen.”

Since 2019, we have been reflecting on these points and adapting the way we implement MSD at ACDI/VOCA. In view of the upcoming 2022 Market Systems Symposium, below is an edited snippet of an exchange among ACDI/VOCA colleagues about how we have continued to address the methodological challenges identified in 2019 in our programming. The exchange is between Dun Grover, deputy chief of party of the TMS Activity in Honduras, and Luca Crudeli, senior director of market systems at ACDI/VOCA and former chief of party of the Feed the Future Mozambique Innovations. At the heart of it is how to deal with the tensions of facilitating (and evaluating) long-term structural changes with an industry bias toward more short-term, behavioral changes that produce faster results. The reflections between Dun and Luca are about how the TMS Activity is resolving this tension and what the team has learned by using a different approach to leveraging system change and measuring results.

Dun – I think we get our understanding of systems change wrong because we are using the wrong mental models. To me, this is evident in the notion that a systems state exists before or after our intervention. Marcus Jenal wrote about this issue when doing a stocktaking of the state of systems measurement.

This notion of a “before” or “after” state gives the impression that projects can change a market system like changing parts in a car. This perspective leads us to develop overly complicated, engineering-like intervention plans.

Rather, if we understand systems as being in a constant state of change and jumping between equilibriums — balanced between agents and forces driving toward change and the status quo resisting change — then it is really a paradigm shift in how you approach development. The work is then much more exploratory and facilitative, pushing different points in the system and seeing how the system reacts.

Basically, our experience working in Honduras teaches us that we need to be careful not to overanalyze or over-plan and to instead analyze what we do during and after the intervention and adapt much more quickly than is “normal” with an annual program cycle.

Image

Fig. 2 - An approach that also looks at structural aspects and mental models is better suited to achieving system change at scale and can help identify new points of leverage

Luca – Dun, you are making good points about where our efforts should go — whether we should spend more time trying to predict where the system will go and how behaviors will change, or focus on improving our own capacity to make sense of the changes, adapt, and improve how we drive change in the direction we desire.

There are a few points of tension in the industry that need to be solved for us to be able to focus our efforts on delivering better systems, rather than better outcomes.

The first is our obsession with producing numbers rather than using numbers for analytical purposes. We are always asked to state how many people we have benefited. The better question is how many people have benefited and will continue to benefit from the changes we facilitated.

This broader question throws a wrench into traditional notions of attribution. It is hard to measure how much your action has changed the trajectory and speed of a moving system. We should be less concerned with attributing the number of participants to our actions and be more concerned with attributing the change itself to our actions and measuring how it is a departure from the system's previous dynamics and trajectories. Particularly, this is the case when the system changes are erratic and nonlinear. It is much simpler to assume the system to be stationary or, at best, in a steady state.

The indicators we use always try to capture static snapshots or cumulative numbers, at best. They rarely look at proportionality or speed of change. They are also less concerned with assessing spillovers from our interventions to other areas in the market system.

Unless we put money into infrastructure or building and running schools (and I often think we should), we are not the creators of change; we are simply mentors, coaches, and advisers. The people in charge are our counterparts. We need to fully recognize this focus, or we will keep operating in a neocolonial bubble.

It would be great to see how other people tackle this challenge during the “Tools Intensive: Clinic Session“ on Thursday, May 12.

Dun – There are some important advances in our MSD community of practice to make the measurement of broader system change more practical and usable. This is so important. How can we manage for systems change if we have no idea if or how systems are changing? At the same time, there is a lot of confusion about systems measurement.

For instance, recently the BEAM Exchange released guidance about the helicopter lens, which is a useful analogy for taking a system view. Too often, I see instances where NGOs project out what they are already doing and imagine all the possible ways their work is changing a system. I see limited value in this siloed perspective.

Instead, I see tremendous utilization value for managers in knowing how the broader system is changing and what the implications of those changes for adaptive action are. The question, “Are we doing the ‘right’ things to catalyze systems change?” is probably the question I hear asked far too little.

Asking this question is challenging. It is true, that some staff are good at keeping their pulse on the broader system and sensing what is changing. But people, myself included, by nature often tend to operate in a sort of tunnel or echo chamber of their own experiences. I think we as human beings, despite those outliers, are quite weak at seeing broader changes; our egos are sort of in direct conflict with that helicopter view.

We need some degree of rigor and checks in terms of other perspectives. That needs to be methodological to balance our instincts to distort. There are an interesting set of emerging evaluation methods that are starting to address this need.

Luca – I agree that the more rigorous our impact measurement systems, the more credible they are, and you need credibility if you want to innovate. But one issue I think we often (if not always) take for granted is the limitations and constraints faced by the project’s implementing teams. Donors do not ask themselves this question; they hire experts. And we do not have a solid incentive to highlight limitations because of competitive procurement. What is actually a feasible management approach to measuring and handling complexity?

The Italian term capire (to understand) comes from the Latin verb capere, which originally meant to capture or hold. How can we develop teams who have the capacity (again, the same root) to capture and hold an understanding of the whole system and a vision for its change?

With Feed the Future Mozambique Innovations, we attempted to shift the focus from producing numbers to probing change and using those numbers to assess whether our probes were changing the system and individual behavior toward a more inclusive equilibrium. I thought the way we formulated and handled probes was manageable and could really help the team with processing and making decisions in a complex context. However, I wish we had more resources and support to build on this foundational approach to develop tools that could help us articulate the bigger picture and better target some structural changes that needed to be brought into the market.

For instance, the Market Systems Resilience Framework, published in 2018, provides some good tools to understand and measure those structural changes. It finally shifts the attention toward measuring the dynamic aspects that drive system behavior and adaptation, as opposed to individual behaviors. I particularly like the fact that the numbers collected through the indicators proposed in the framework are just an input to the analysis of how systems are changing from a reactive to a proactive orientation; they are not the goal. I am puzzled that we are using this approach only when we talk of resilience though. Should we not always try to improve the capacity of market systems to innovate, adapt, and bounce back from shocks?

Dun – Yes. I know there is a temptation to want to "wrap up" systems change as all figured out, but I think the reason it matters is many of us are still not that comfortable with the state of the world today. It is hard to say “mission accomplished” — that the changes we as an industry are facilitating are really having the lasting, broad scale of impact that we hoped for. Instead, it seems we keep falling into short-term cycles of thinking.

This shorter-term thinking is deeply embedded in our implementation approaches. Let’s take a typical tool that we use in MSD: the results chain. The tool normally requires you to indicate who does what differently. This narrows the focus to the micro-level or the individual actors or behavioral changes that we want to see in the system.

But what about real, structural change? Changes in networks? Institutions? Or social norms? Do those types of changes fit neatly in a linear result chain of who does what? I don’t think that they do, naturally.

Implicitly, the rationale for their exclusion seems to be a forced trade-off. Since it is harder to measure those structural things, we only measure them indirectly once behaviors change. But how do you manage for structural change when the second-order behavioral changes are likely years (if not decades) out?

I believe this short-term thinking systemically biases our interventions away from those necessary structural changes where you have real leverage for long-term development to those that achieve short-term results.

Luca – Dun, we are on the same page on many fronts. Here are some topics that I propose we can try to “unwrap” during the “Tools Intensive: Clinic Sessions” we will be hosting on Thursday, May 12.

First, how do we broaden our understanding and measurement of the system from a narrow focus on actors and behaviors to a more structural understanding that includes important factors like the distribution of productive and financial assets, voice, agency, innovation, and all the fundamental elements that ultimately determine the long-term levels of competitiveness and inclusion in a market system?

Second, how can we establish baselines that are compatible with dynamic, ever-changing systems? For instance, when we start a new project, how do we better understand the long-term, or even medium-term, trajectories of change in those factors? Development is path-dependent, and we need to acknowledge those trajectories to better understand what is possible for change and to better contextualize our contribution to that change.

Third, what is the cost-effective and operational balance between formative studies at the beginning of a project and probing and learning during the implementation of the project? I still don’t understand why so much emphasis is placed on early deliverables when a new project starts and relatively little after the project is underway.

Part of addressing these challenges is figuring out how to balance between learning and analysis and action and adaption without overwhelming your team or undermining local capacity and the clients’ patience at the same time. I don’t think we should take the management dimension out of the equation; we should talk more about how we can make implementation more effective, and we need to develop knowledge products that can be really used for action.

Dun – Good points, Luca. Let’s see if we can discuss more on this during the Market Systems Symposium this year based on the TMS Activity’s experience in Honduras, and we can learn from what others are doing.