Private Sector Engagement Still Pays Off Five Years Later

Image

This brief, based on sustainability research led by Tashfiq Ahsan and Mehrul Islam, was written by Emily Janoch and originally posted on Agrilinks.

What happens when you build gender equality into a sustainable market solution? That solution lasts and grows for years after projects end. For Taslima in Bangladesh, the result means, “I can save time, spending more time with my family …. SDVC’s collection point has made my life so much easier. I no longer need think about or send some of the local market… it’s truly a blessing.”

It’s not just that female producers save time — they also earn more money. Beyond that, when you do it right, businesses at all levels grow. Abdul Karim Koel runs a collection point like the one Taslima sells to. He used to collect 40 liters of milk a day and earn $50.64 a month. By 2016, it was up to $109 (11,200 Bangladeshi taka (BDT)) a month. By 2021 — five years after the project closed — he was earning $1,740 per month, even after coping with the shock of COVID-19.

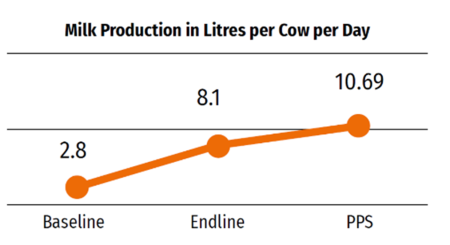

Five years after the Strengthening the Dairy Value Chain (SDVC) project ended (the project ran from 2007-2016, and served 26,138 farmers with funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation), farmers are earning more money, producing more (and higher quality) milk and selling their milk to more companies. Women are making more decisions and have even more access to markets than they did when the project ended in 2016. This is true despite the fact that COVID-19 dropped demand for milk by 40% and closed markets for weeks at a time.

What impacts lasted over time?

-

Image

- Women are making more decisions. Five years after the project closed, women are making 75% of the decisions about spending money jointly with their spouses, up from 72% when the project closed, and 66% at baseline. In a world where COVID-19 pushed women’s rights back by a generation, not only maintaining, but increasing, decision-making power is remarkable.

-

Image

- Markets are still working — even during shocks. Despite the profound impact of COVID-19, 95% of SDVC producers were still selling to the local collection points that were one of the key solutions in SDVC. Those centers make it easier for women to access resources and sell milk because they are a one-stop shop close to home. In fact, 90% of SDVC producers are women.

- Markets kept reaching people and women during COVID-19. In COVID-19, those collection points bought as much milk as they could process — and made sure to buy slightly smaller amounts from as many farmers as they could so that every producer could keep earning money during the crisis. Many collection points started sharing COVID-19 information and offering credit so farmers could stay in the market and keep selling milk.

- More private sector partners buy local and buy from women. In addition to BRAC Dairy, CARE International’s original private sector partner for SDVC, the three other major national milk processors are now also buying from SDVC collection points and from women. PRAN dairy even went from sourcing 10% of their milk from women to 14% from women.

- Services are not only still running, but they have also expanded. BRAC nearly doubled the number of local collection points using this model — adding 108 new centers to the 111 CARE had built. PRAN built 101 centers. Both BRAC and PRAN plan to build even more in new regions of the country.

How did it happen?

- Make it easy for farmers — especially women — to get supplies and sell milk. Collection points provide a place close to home where producers can get a transparent and fair price for milk, access training and get medical supplies for their animals. CARE built 111 by the end of the project. By 2021, private sector partners had built 209 more, and they are still expanding. This is especially good for women, who have a harder time travelling far away from home. The people who sell supplies increased the number of their female customers by 20% since 2016.

- Train workers who can earn an income. The project trained 26,138 dairy producers — and 90% of them continued to improve their skills in the five years after the project closed. That’s partly because of the 8,480 extension agents the project trained, and the 500 Krishi Utsho vendors who are earning a good income selling supplies people can afford.

- Invest in closing the gender gap. The whole project was designed to serve female producers and meet their market needs. That meant finding solutions to get women better market information, more decision-making power at home, access to services they could afford and travel to, and making sure that women were at the core of the project. Of the SDVC producers, 90% are women.

- Build market links. SDVC didn’t just connect women to one company. They helped launch a whole network of market actors, from livestock health workers to collection centers to local businesses who could sell affordable and quality inputs. They worked with several private sector companies who could buy the milk so that people weren’t locked into just one option (and kept the market competitive).

- Make the business case. The project succeeded so well in building a profitable model that private companies are investing their own money in scaling the model. That’s because they get a more sustained supply, better quality milk and more milk they can sell in the market. They care so much about keeping this working that they made sure to take care of producers even during the worst of COVID-19, because that’s good for their businesses.

- Invest in data and learning. Not only did the project focus on data while it was working, we also used a small grant from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to go back five years later and see what was still working. That’s part of CARE’s bigger investment in understanding what impacts are sustainable over time.

What didn’t last?

- Technology for its own sake. While the technology solutions in new Digital Fat Testing (DFT) Machines and Geographic Information Systems (GIS) mapping were a big part of the project, that’s not what has sustained over time. Because it’s hard to replace parts in the DFT, the companies are switching to other solutions as those machines age out. Companies found the GIS mapping too complex to maintain over time because they were not getting enough benefits from it.

- Companies holding the whole supply chain. Over time as the local milk market grew, producers were able to make money selling into the local market, so didn’t go only to the large, national companies. However, when COVID-19 closed local markets, the large companies were the only people buying milk, and they saw a surge in their supply.

Want to learn more?

Read the post-project study and brief, the endline evaluation or any of the project stories and case studies.