A New Way Forward for Southern Africa: USAID Pilots a New Approach to Private Sector Engagement

Image

This blog was written by Kristin Kelly Jangraw and Emily Langhorne of USAID INVEST.

On the outskirts of Johannesburg, in the eastern part of Soweto Township, lies South Africa’s most famous street. Vilakazi Street, once home to former South African President Nelson Mandela and Archbishop Desmond Tutu, is the only street in the world to have housed two Nobel Prize winners.

Historically, Soweto needs little introduction. A worldwide symbol of the South African people’s resistance against the apartheid regime, the township’s 1976 protests against the mandatory use of the Afrikaans language in school resulted in nearly 200 deaths at the hands of the police.

Nowadays, visitors stroll on Vilakazi from the Hector Pieterson Museum to Mandela’s home, soaking up the history. Artists, performers, and restaurants, catering to the many walking and bus tours, line the neighborhood’s streets. Elsewhere in Soweto’s Orlando suburbs, residents have used their newly gained affluence to expand their homes or build new ones, purchase new cars, and dine at upscale restaurants.

However, less than a few miles away, many of Soweto’s other suburbs, such as Klipspruit, look very different. Here, unpaved and narrow alleyways weave their way past overcrowded homes, cramped shacks with dirt floors and metal roofs. Neighborhoods like these, which are still home to many of Soweto’s 1.2 million residents, have limited electricity and no indoor plumbing.

The story of the two Sowetos mirrors the larger story playing out in South Africa. Each year, millions of tourists come to visit its wineries, waterfronts, national parks, and historical sites. Likewise, investors and multinational companies seek out opportunities in one of Africa’s most diversified economies that has deep connections to global markets and an advanced financial and banking sector.

Despite South Africa’s wealth and beauty, the country faces serious challenges. In 2019, nationwide unemployment was around 28 percent, and in 2015, about a fifth of its population lived on less than two dollars a day. The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated these challenges.

In addressing these challenges, USAID Southern Africa (USAID/SA) aims to use the country’s strengths against its weaknesses.

Rather than looking inward to solve problems that have traditionally fallen under the scope of international development agencies, the Mission is looking outwards to solve them by working hand-in-hand with the private sector. In designing market-driven solutions, USAID can use its limited funding to achieve better, more sustainable development results, deepen local markets, and ultimately help countries on their journey to self-reliance.

With its deep pools of capital and talent, the private sector is an indispensable partner, but it is also massive and complex. The possibilities for partnerships are too many to count, making it no small task for USAID staff to choose which partners to engage or which relationships to cultivate.

USAID/SA recently piloted a methodical approach for narrowing down the overwhelming universe of options to a promising few and using those options to incorporate a private-sector engagement strategy into its Regional Development Cooperation Strategy or RDCS.

Development Cooperation Strategies are the beating heart of every USAID Mission’s strategic planning and budgeting process. They are done at a country level (a CDCS) or a regional level (RDCS), and each is typically a five-year strategic plan that lays out the operating context, goals, expected results, and performance indicators from the Mission’s point of view. Partners, grant-seekers, and implementers look to these publicly-available documents to understand Missions’ priorities and the programming and funding streams that are likely to flow from them.

RDCS and CDCS documents provide an impressive level of detail and transparency. Each is organized around an overarching goal, which is broken down into a handful of development objectives, and then broken down again into subgoals. A development objective focused on inclusive and sustainable economic growth, for example, could be broken down into subgoals to improve the regulatory environment for businesses, help small businesses become more competitive, and increase international trade.

When USAID/SA began designing its most-recent RDCS, staff knew that integrating a private-sector engagement strategy during the planning stage would lead to better results. However, they needed a methodical way to do it.

“Our goal was to increase collaboration with the private sector, including partnerships over the lifetime of the RDCS,” said USAID/SA’s Jacques Swanepoel. “We wanted to identify the opportunities for private-sector involvement that had the highest potential. We wanted to know: where is the lowest-hanging fruit — the most feasible private-sector solutions in our portfolio? And we wanted to walk away with tangible ideas to partner across our portfolio.”

USAID/SA, through the INVEST initiative, put out a request for proposals to support this process. INVEST was designed to ensure that USAID can partner effectively with specialized firms, regardless of whether those firms have worked with USAID before. INVEST often onboards what USAID calls “new and underutilized partners” — firms with valuable expertise that have not worked extensively with USAID before. In this case, USAID and INVEST selected Genesis Analytics — an economics-based consulting firm. Headquartered in Johannesburg, it has an intuitive grasp of the local landscape and a strong network of other private-sector contacts.

“Having a local partner was a huge asset,” says Jessamy Nichols of INVEST. “There wasn’t a ton of desk research that had to be done up front. Genesis understood public sentiment, what was going on in the news, and what NGOs should be involved. That fluency with the local context made the market-based approaches they suggested realistic and responsive to market conditions.”

INVEST has worked extensively with new and underutilized partners, and these partners have demonstrated over and over the value they can offer to USAID. However, until this piece of work, INVEST had not yet seen a new or underutilized partner work with USAID in this way — supporting an internal process, helping with the RDCS, and building capacity within the Mission.

“This is one of our first pieces of work supporting an important internal strategy process for a USAID Mission,” says Kristi Ragan, Chief of Party for INVEST. “We have been seeing more and more evidence that new and underutilized partners can be invaluable to USAID, and we have worked closely with them on facilitating investment and closing transactions, for example. But before this, we hadn’t seen them get inside and deliver direct value to the inner workings of USAID Missions and USAID planning.”

Genesis was very familiar with the South African context, and they dug in deep to understand USAID’s goals. “We got to know the RDCS that the Mission has been relying on to shape their work as well as USAID’s Private Sector Engagement Policy framework. We also looked to USAID’s thinking on the Journey to Self-Reliance. They have a graph tracking countries against capacity and commitment for private-sector activities, and we used that thinking to identify priority development areas,” says Genesis’s Marc Dunnink.

In addition to doing their homework, Genesis’s team took a highly collaborative approach with the Southern Africa Mission. “A lot of new partners that come on board are going to go crazy around how much information they can find about different countries that USAID works in, but things are very fluid on the ground,” says Jacques Swanepoel of USAID/SA. “The implementation is really done within the technical teams who know what they want to drive: What are the development objectives? What are the issues? How are they progressing? What are the remaining challenges? Talking with the technical teams at the beginning and really battling that out is crucial for an engagement to be successful.”

As it began working closely with the Mission to set its strategic goals, Genesis recognized that incorporating private-sector solutions would require a two-phased approach. The first phase would identify which development challenges to address, and the second would identify the most promising opportunities for USAID to address these challenges in collaboration with the private sector. In short, the first phase focused on what to do, and the second on how to do it.

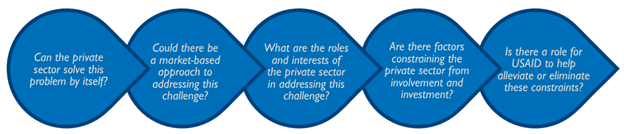

To start, Genesis worked with four technical teams at the Mission to understand their priority development challenges. Genesis then developed criteria to choose which of these challenges could benefit most from engagement with the private sector. Genesis used the five questions laid out in USAID’s Private Sector Engagement Policy to guide the creation of the criteria:

“We used a fairly simple framework,” says Dunnink. “We took every development challenge we’d uncovered and rated it across those criteria on a scale from one to three: whether there was a clear opportunity, whether there was room for consideration, or whether there should be hesitation.” This framework enabled Genesis and USAID to shrink the universe of possible approaches, pulling out those opportunities with the greatest chance of success. (Take a look at the framework)

Once Genesis and USAID selected which development challenges to focus on, Genesis shifted to conducting the research necessary to implement phase two: they had to discover the root causes of these development challenges.

“We looked at the critical underlying factors, how they fit into a market ecosystem, and where the deficits were,” says Dunnink. “Then we started coming up with possible solutions. With an understanding of the market environment and what the private sector would be willing and able to do, we started designing market-based approaches targeting those root causes and failures in the market system.”

Genesis then consulted with local stakeholders already working on these issues to check its thinking about the potential effectiveness of and barriers to implementing these market-based approaches. By bringing in stakeholders at this stage, Genesis created an opportunity to gauge the appetite of potential implementation partners and laid the foundation for successful future collaboration.

Next, Genesis had to decide which of these approaches would have the greatest impact. To frame this decision, Genesis evaluated the selected market-based approaches against a second framework. It evaluated feasibility, impact, and additionality.

Donors who are serious about collaborating with the private sector must consider additionality. It is a measure of whether a donor’s actions or funding make a difference in the way capital flows into a sector or market. Development agencies want to maximize the private capital they can leverage, but they also must avoid subsidizing deals or investments that are commercially viable on their own and would happen even without their involvement. In this case, Genesis adapted a framework from the Donor Committee for Enterprise Development to assess additionality.

The final product was a short, prioritized list of promising approaches that were ready for USAID to implement. “We did create a comprehensive report, and we hope it gripped the attention of the readers, but we also provided a narrow set of actionable recommendations,” says Dunnink. He hopes this will be particularly valuable to busy USAID staff, who need to see the comprehensive report to trust the rigor behind the process, but who really need a concrete, doable way forward to be effective. Throughout the process, Genesis maintained a collaborative, iterative process with USAID, ensuring that Genesis’ work would evolve with USAID’s changing priorities.

“As our strategy is implemented over the next year, our technical officers will use these recommendations to form or expand activities,” says Swanepoel. “What we are left with is — yes, a massive document — but also a set of actionable development solutions that we can take forward and use. With a lot of assessments and evaluations I’ve seen — you just shelve it; you don’t truly use it. That’s what makes this one different and I’m excited about that.”

USAID/SA is not unique: Every USAID Mission faces the challenge of integrating private-sector engagement wisely into its CDCS or RDCS process. Now, Swanepoel and the INVEST team are working together to replicate this approach with another Mission in its RDCS process, says INVEST’s Amanda Bartels. “We kicked off this process with a conversation between the Mission and Swanepoel, who shared what he had learned piloting the approach in South Africa. We also shared the Statement of Objectives and Request for Proposal we used to recruit support as well as some of the key products that Genesis provided. We will adapt the process we piloted in South Africa to a new set of priorities and what the Mission is trying to achieve in a different context,” she says.

“South Africa is a transition country, and it is well-advanced on the Journey to Self-Reliance,” says Swanepoel. “It has the second largest economy in Africa and a thriving and prosperous private sector. What you can do with this type of assessment depends on the maturity of the private sector in the country you’re working in, and the results would look totally different in places where the private sector is not as mature. You would have to adapt or retrofit the assessment based on what your country looks like economically. But what is important is that we now have a framework to do that.” Other Missions that are interested in adapting this work can find the scope and frameworks, and they will find a willing collaborator in Swanepoel.

This type of work — improving strategic planning, mobilizing private investment, collaborating effectively with new partners — may seem dry, but it has the potential to be very powerful. By making USAID more effective and drawing in resources that are aligned with its goals, it has the potential to help address the root causes of poverty, hunger, sickness, and other suffering. The work may start out on spreadsheets but it will be measured in human impact.

To hear more from Genesis Analytics about their experience working with USAID, check out Voices from the USAID Finance and Investment Network: Genesis Analytics.

If you have finance or investment expertise and are interested in working with USAID, please reach out to INVEST. The initiative can help you identify subcontracting opportunities, navigate the USAID subcontracting process, get a handle on USAID’s priorities and style, and implement your first subcontract successfully. Learn more at www.usaid.gov/INVEST or email INVEST.

This post is made possible by the support of the American People through the United States Agency for International Development. The contents of this blog are the sole responsibility of INVEST implemented by DAI and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government.