Looking Ahead: The Future of Economic Strengthening

Promising Practices

In 2008, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) defined economic strengthening (ES) as “[t]he portfolio of strategies and interventions that supply, protect, and/or grow physical, natural, financial, human, and social assets aimed at improving vulnerable households cope [sic] with the exogenous shocks they face and improve their economic resilience to future shocks.” That is a tall order; however, we are seeing an increasing demand for holistic programming to respond to the needs of orphans and vulnerable children (OVC). A growing body of evidence points to risky behavior by orphans and vulnerable children seeking to meet immediate livelihood needs, such as accepting “gifts” from older males in return for sexual favors and migration.

Here, we can begin to understand what the problem is. We know there is a call for an innovative “portfolio of strategies and interventions” aimed at improving vulnerable households’ ability to cope with shocks, but what are they? What evidence is there to prove that ES models and approaches even work? Well, the jury is still out; however, we will explore a few areas that have seen promising practices for OVC and where these ES trends may take programming in the future.

Organizations like Catholic Relief Services (CRS) have begun integrating savings-led microfinance programs (otherwise known as savings groups) directly into OVC programming, which can increase resilience to shocks as well as asset building. A 2010 assessment of their programming in Zimbabwe and Rwanda showed that participation in savings groups (SGs) enabled participants to stay in school; improve their nutrition; improve their money management skills; and increase their confidence, self-esteem, and sense of empowerment1.

We have also begun to see programming that provides incentives for OVC caregivers to “invest in economic assets that will support their [orphans and vulnerable children] current and future well-being.” Further evidence has pointed to positive outcomes from caregiver participation in SGs. Orphans and vulnerable children can be affected by these outcomes directly or indirectly: directly, when caregivers use savings and credit to benefit a child’s nutrition, health, education, and living conditions, and indirectly through strengthened social ties leading to assistance with childcare from other SG members and to asset accumulation.

Skills training is also considered an essential intervention for ES but is most effective when training is directly linked to income earning opportunities. Researchers have documented cases in which participants sold tools and equipment provided after training because the revenue from these sales was more valuable than attempting to earn income from the skill that was acquired through training.

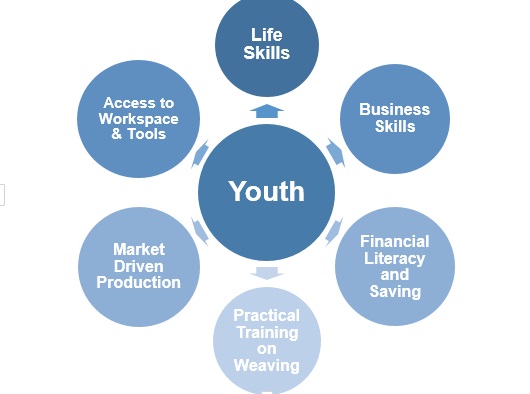

MEDA’s EFACE (Ethiopians Fighting Against Child Exploitation) project offers skills training on weaving techniques to young weavers in the textile industry while also offering comprehensive financial capabilities training on financial education, business, and life skills. These three areas were selected based on youth’s needs for better understanding of what financial services are available to them and for business practices and life skills that will equip them on their journey to adulthood2.

Well-designed and implemented loans and market linkages targeted at older youth (aged 18+) can also improve their long-term economic security. Loans have yet to be “proven” as a scalable means of increasing income generation for vulnerable children, but they can be effective when coupled with training and responsible client selection processes. Ideally, such loan disbursement should avoid distorting the market; linking individuals or groups to existing institutions is more sustainable than short-term financing through a project or non-governmental organization. Research found that the effectiveness of income generating activities, like that of skills training, is largely based on the quality of market research and the skills training in place. Identifying entrepreneurial individuals and maximizing support to households and communities increases long-term success of entrepreneurship initiatives, creating ownership and ensuring that children or other household members can take over if adult caregivers become sick or die.

Cash transfer programs targeted directly to OVC and their caregivers have gained attention because of their impact on the educational, health, and nutrition outcomes of children. Research has shown that cash transfers can reduce sexual risk-taking behaviors among youth, particularly girls. We have seen programming in South Africa, where cash transfer programs are channeled through bank accounts, further promoting financial inclusion and building OVC financial capabilities.

Future Directions for Economic Strengthening Programming

Additional research, testing, and sharing of learning is required. There is emerging evidence that combining skills training, savings-led microfinance services (i.e., savings groups), promotion of entrepreneurial initiatives, and cash transfer programs can aid orphans and vulnerable children and their households in absorbing the frequent social and economic shocks that arrive in their lives. Though ES programming for orphans and vulnerable children is still relatively nascent, we can anticipate that future programming will likely focus on the above-discussed core strategies and better innovations to address the needs of increasing numbers of vulnerable people. Promising practices, like those being carried out by IRC, CRS, MEDA, and others will be closely watched, documented, and discussed.

What are the future directions on holistic ES programming that you see?

1 CRS’ Rwanda program added SGs to an existing package of services for OVCs aged 13 to 18 who were child household heads. These services included education, health care, psycho-social support, nutrition training, vocational training, and business skills training. OVCs benefited from the program by acquiring skills to improve business and manage money, pay into Rwanda’s national health insurance, purchase animals and land plots, and buy clothes and school materials for themselves and siblings.

2 Over 100 youths went through the Building Skills for Life training and were linked to the Ethiopian Bureau of Women, Youth and Children Affairs and the Medium and Small Enterprises office. The latter, in turn, has a program for the youth to receive their working tools and production workspace in a government-availed location. This linkage, facilitated by EFACE, means that the trained youth have tools and workspaces for their production activities—and they will either sell the products themselves or sell them to a store/weaver/retailer, etc. Additionally, the project piloted an agricultural rural sales agent model. The EFACE project targets rural youth (ages 14–17) for a youth economic development intervention with the intention of providing youth with access to safe and reliable work. Under this intervention, youth sales agents have received Building Skills training and agri-kits that include a scale, a backpack, calculator, notebook, and other relevant materials to sell agricultural supplies. The youth were trained on technical and entrepreneurial subjects relating to business development and were provided with start-up kits to transition them from exploitative labor to productive work as entrepreneurs. A recent program assessment of this intervention found that youth have developed entrepreneurial skills and were engaging in diverse business activities.

This blog series was sent courtesy of Microlinks, part of the Feed the Future Knowledge-Driven Agricultural Development project. Its contents were produced under United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Cooperative Agreement No. AID-OAA-LA-13-00001. The contents are the responsibility of FHI 360 and its partner, the International Rescue Committee, and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government.