How a Circular Economy Can Cut Greenhouse Gas Emissions by One-Third

This post was written by Gillian Caldwell and was originally published on Climatelinks.

In the United States, we love our stuff. The average American uses twice as many non-edible goods now as we did 60 years ago. We also generate twice as much waste per day — 4.5 pounds — as we did 40 years ago, thanks to a lot more (carbon intensive!) plastic and other packaging, and a far greater tendency to make items designed to wear out quickly. (Can we say planned obsolescence?) Worst of all, for every full household garbage can at the curb there are an estimated 70 garbage cans worth of waste generated along the production process.

In fact, the United States leads the world in waste production, and much of the rest of the world wants to follow our example thanks to omnipresent media globally driving home the need to consume bigger and better. Where will that leave the planet? In the past three decades alone, one-third of the planet’s natural resources have been consumed — clearly an unsustainable pace. Humans use as many ecological resources as if we lived on 1.75 Earths. Even industries like renewable energy created to ease other environmental problems are set to become a part of this problem if we don’t get ahead of it. Obsolete renewable energy equipment is expected to grow exponentially over the next 30 years. And minerals like cobalt and lithium needed for battery production are becoming harder and more dangerous to find and extract, yet recycling systems have not been put in place for critically needed materials to fuel the renewable energy revolution.

Transition from a Linear Economy to a Circular Economy

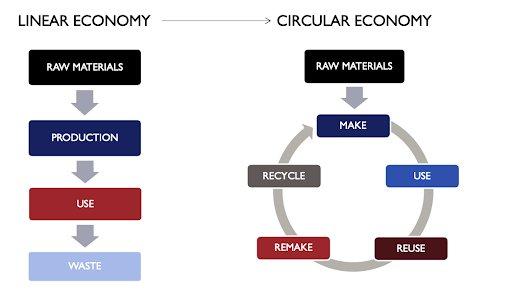

So how do we change course? How do we start living more responsibly? We can shift to a “circular” economy. But what is a circular economy? In a circular economy, products, parts, and materials have multiple life cycles and re-entry points into the market as they are systematically recovered, repaired, reused, and remade. Batteries, for example, are recharged until they reach the end of their life and then they are disassembled and their mineral components recovered and reused. Where the “linear” economy disposes of waste in landfills, the circular economy creates multiple opportunities for “return cycles” or “loops” that avoid disposal. Nature itself is a perfect example of a circular system, and there is a lot to be learned from that example.

Image

Transition from linear to circular economy. Credit: Adapted from Wikimedia Commons by Catherine Weetman.

Renewable Energy

For the renewable energy supply chain to be resilient and sustainable, we must transition from a linear economy to a more circular economy. Solar, wind, and battery equipment must be manufactured, deployed, and decommissioned in a responsible way so that the parts can recirculate without the same level of additional mining and waste. USAID seeks partners to support transformational policies and initiatives, build human capital and institutional capacity, and develop new innovations and models to address waste challenges while creating economic value and jobs. This, in turn, can help drive a circular economy that is gender inclusive, reduces waste, makes the supply chain more resilient, and extends the life of parts.

At current linear rates of production, the annual need for critical metals for renewables could outpace supply and endanger the transition to a clean energy economy. Transitioning from a linear economy toward a more circular economy will secure the United States and its allies’ long-term supply chain and stem price shocks of critical minerals needed in renewable energy equipment.

The circular economy could also generate an estimated $4.5 trillion in additional economic output by 2030. An International Renewable Energy Agency study estimates a value of $15 billion injected back into the economy just from the recovery of raw materials through recycling or repurposing used solar photovoltaic panels. Overall, circular economy strategies that rely on repairing and refurbishing products minimize our use of resources and — very importantly given the climate crisis — can cut global greenhouse gas emissions by 39 percent.

Application of the circular economy framework to renewable energy is in its earliest stages. Building on capabilities of USAID’s Scaling Up Renewable Energy (SURE) program, we published a guide titled Clean Energy and the Circular Economy: Opportunities for Increasing the Sustainability of Renewable Energy Value Chains. USAID intends to mobilize resources and stimulate innovation through pilot projects ranging from incorporating circular economy considerations in renewable energy procurements to developing incentives for the private sector in coordination with partner nations to invest in recycling, repair, and/or reuse. As the clean energy transition accelerates, USAID will partner with the private sector and utilize circular economy approaches to ensure sustainable, equitable, and environmentally sound practices are used across the renewable energy supply chain.

For example, in May 2022, USAID sponsored a delegation of public utility officials from Bhutan, India, Nepal, and Sri Lanka on an executive exchange to learn about renewables integration and power markets in Europe. A featured stop on their tour was at PV CYCLE, a non-profit, member-based organization that offers collective and tailor-made photovoltaic panel waste management and legal compliance services for companies and waste holders around the world. The officials were able to take the lessons from the PV CYCLE example back to their utilities and ministries in South Asia.

Ocean Plastic Waste

Of course, waste from the renewable energy industry is only one piece of the overall problem of our disposal culture. Another large contributor is single use plastics and plastic packaging. Roughly 11 million metric tons of plastics make their way into the world’s oceans every year, leading to many threats to marine ecosystems — and the people who depend on them.

Most ocean plastic pollution comes from rapidly growing cities and towns along rivers and coastal areas where reliance on single-use plastics and flexible plastic packaging produces high volumes of waste that are not easily recycled, or even recovered. In many locations, there is no infrastructure set up for recycling. The most effective way to immediately address ocean plastic pollution is to stop it at the source: on land. USAID is working to reduce the proliferation of single-use plastic packaging and improve local solid waste management systems to capture and recycle waste. We anticipate significant entrepreneurship opportunities for recycling that can galvanize local economies and support growth of women-owned, diverse and inclusive SMEs.

For example, USAID’s Circulate Capital Partnership is a blended-finance partnership to catalyze investment in the recycling and waste management value-chain — part of the circular economy — in South and Southeast Asia. This partnership has already mobilized over $100 million in investments.

About the Author

Gillian Caldwell serves as the Chief Climate Officer and is responsible for directing and overseeing all climate and environment work across the agency. She also serves as Deputy Assistant Administrator, overseeing DDI’s Center for Environment, Energy, and Infrastructure and the Office of Environmental and Social Risk Management.

Ms. Caldwell has worked to protect human rights and the environment throughout her career. Prior to joining USAID, she served as the CEO of Global Witness, which has a focus on tackling climate change and deploys investigations into corruption and natural resource extraction to drive systems change worldwide. From 2007-2010, she launched and led 1Sky, a highly collaborative cross-sector campaign with over 600 allied organizations to pass legislation in the U.S. to address the climate crisis. Gillian also has extensive experience consulting in the areas of strategic planning and organizational development with over 70 non-profits, foundations, and universities.

Ms. Caldwell has a B.A. from Harvard University and a J.D. from Georgetown University, where she was recognized as a Public Interest Law Scholar. She has received a series of awards recognizing her work as a leading global Social Entrepreneur.