The Art of Collecting Qualitative Life Histories, and What They Can Teach Us About Resilience

Image

The golden rule is this: research fieldwork never goes as anticipated. That doesn’t necessarily mean it will go worse than expected, but it will be different. The parts which you may not even have imagined would be tricky—such as ensuring the respondent is comfortable and there is nobody else around—suddenly become issues on which the success of the research depends. How do you ask the respondent’s elderly parent to leave without being rude? The real world is far from that described in books on research methods.

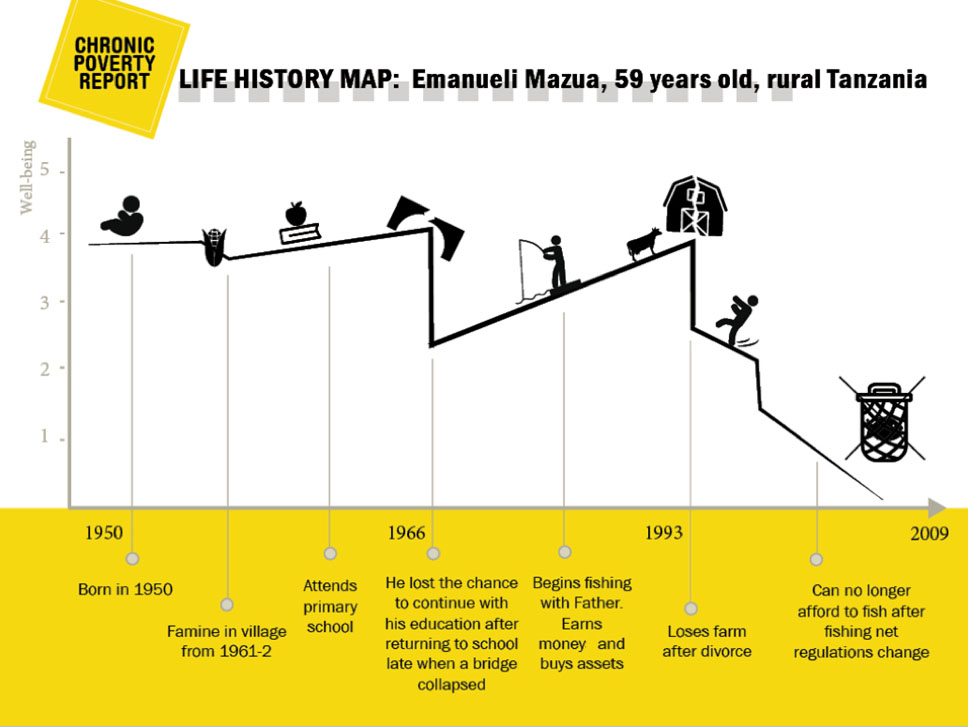

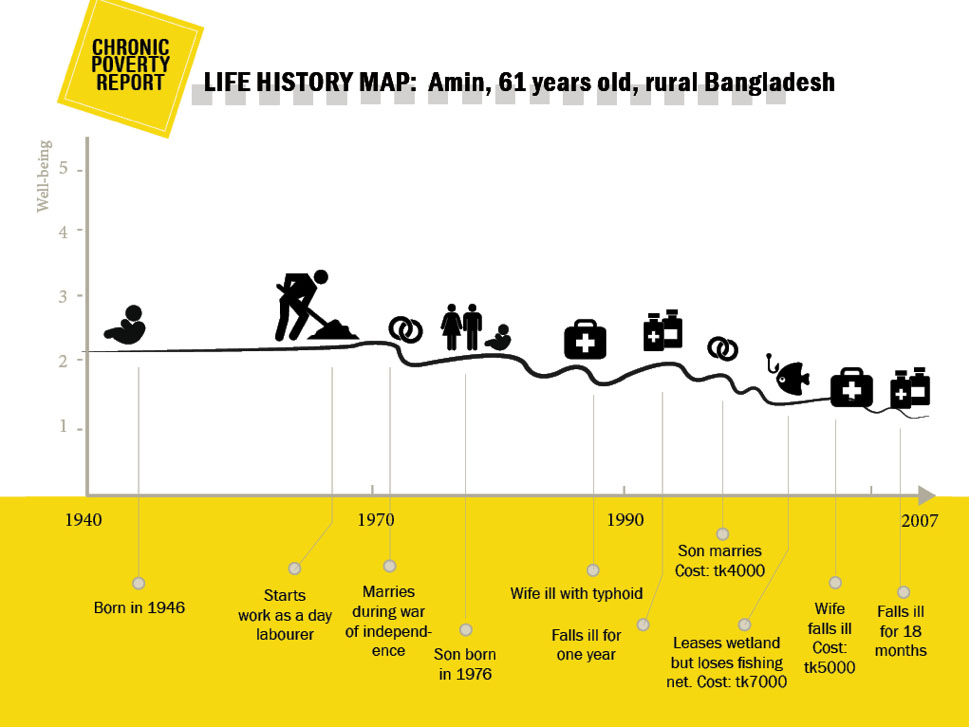

As part of ODI’s research into poverty trajectories, conducted for USAID through the LEO activity, Moses and I have been collecting life histories from female and male household heads in Kole District in northern Uganda. Life histories are a form of open-ended interview which ask people about five key stages over the course of their lives to capture the dynamic reality of poverty over time. Life histories identify periods of improvement, times which have been tough, and periods where really not much has changed. Why did people’s situation deteriorate? How did it get better? How, despite illness, drought, or some other shocks, did they manage to protect their situation? The output from these interviews are a narrative and a life history ‘map’, such as the two below.

For USAID, interest in life histories, as collected by ODI’s Chronic Poverty Advisory Network, is because of the in-depth insights they can reveal about the resilience (or lack thereof) of individuals and their households. Life histories can be particularly valuable as a research method when used in tandem with analysis of national panel data sets (surveys which re-visit the same household at several points in time). This is because life histories enable further investigation into what may have contributed to or caused positive or negative changes. Households close to the poverty line frequently move out of and/or back into poverty; understanding the reasons for this can prove very useful for program designers and poverty reduction strategies. For example, click here to see how one development program in Bangladesh uses a life history approach to assess the outcomes of its work.

In addition, recent analysis for The Chronic Poverty Report 2014/15 of national panel datasets for Uganda reveals that escaping poverty is not a one-way street; many households escape poverty only to return to it again. That is, they ‘backslide’ into poverty. For example, at a national level, around 50% of Ugandan households that escaped poverty between 2005/06 and 2009/10 had returned to living in poverty by 2010/11. Life histories are one way of investigating this backsliding phenomenon further; in particular, to explore that all important ‘why’ question.

But the practice of collecting life histories—and using them to answer research questions—is much trickier than it sounds.

Initially there is the challenge of explaining to people what you are doing and why. Particularly in an era of large-scale surveys and questionnaire data collection, respondents can find the idea of sitting down and talking to you about their lives to be slightly strange. Common responses are: “But nothing much happened!” Or, “I can’t remember anything from my childhood!” Putting myself in their position, I’d certainly find it extremely strange if somebody asked me to do the same: my life is really not that exciting and I would have no idea why somebody would want to spend 90 minutes listening about it. In fact, not being a natural talker, I reckon my life story could be over in ten minutes, given similar circumstances.

This is where the skill of qualitative research comes in. Not only is it essential to gain people’s consent, but it is crucial that they feel at ease and realize you are genuinely interested, even in aspects which may seem very mundane. In particular, it is important to get the right balance between open questions, which provide people the space to describe their experiences; follow-up questions, which clarify and gain more details of certain events and processes; and prompting questions which ensure that, in each of the five stages of the life course, no major events or experiences, such as ill-health, have been forgotten.

For more ‘tips of the trade’ on collecting life histories, along with workshop exercises and sample questions, view this briefing note here.

Getting back to Uganda: keep an eye out for the Uganda case study on ‘backsliding’ and the links to resilience, to be published later this spring. Moses and I are extremely grateful to the women and men who gave up their time to describe their life trajectories to us. They may never directly benefit from this research, but hopefully the insights which they freely gave will ultimately help to improve future programming. Their experiences reinforce the notion that concepts and theoretical debates around ‘resilience’, ‘poverty dynamics’ and ‘impoverishment’ ultimately only have meaning in so much as they relate to people’s lives.