Mapping the Chain: Looking Beyond Production for Inclusive Agriculture Development

At the 2016 White House Global Development Summit, President Obama announced that he had signed the Global Food Security Act, codifying the U.S. Government’s commitment to global food security into federal law and ensuring that initiatives like Feed the Future “endure well into the future.” As we look toward the future, it is important to consider the evidence and lessons learned over the first five years of implementation — from USAID Missions, partners and other key stakeholders — that will serve to further strengthen the impact of this important initiative.

The U.S. Government recently released a new Global Food Security Strategy, which builds on Feed the Future. The strategy places an even greater emphasis on an integrated cross-sectoral approach that improves agriculture and food systems. Just as important, the strategy ensures that new programming is built on a deeper understanding of women’s and men’s roles throughout these systems. A key lesson learned from the first five years of Feed the Future is that providing access to inputs or knowledge of agriculture production is not enough: expanding women’s skills, roles, and market relationships in agriculture and food systems is critical for both women’s and men’s participation in and benefit from inclusive agricultural growth.

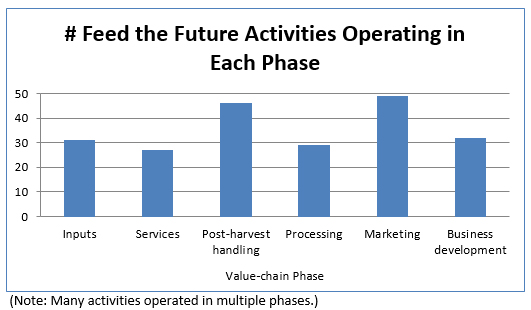

To understand the evidence and gather lessons learned, the Leveraging Economic Opportunities (LEO) activity performed an internal, informal landscape analysis of existing Feed the Future efforts in agricultural value chains beyond production. The 67 activities included in the analysis are those for which there was sufficient publicly available information to identify programmatic approaches after having been identified through keyword searches in the Feed the Future Monitoring system across 19 countries. The landscape analysis divided the non-production value-chain phases into six main categories — input development, service provision, post-harvest handling, processing, marketing and business development.

Across the 67 activities, marketing and post-harvest handling are the most common phases where Feed the Future programming worked. Programming most often involved:

- training and organizational capacity building, especially business skills;

- creation of market linkages, ranging from informal events to bring actors together to formal business contracts; and

- provision of technology or infrastructure, ranging from small storage bags to large food processing equipment for associations or enterprises.

Many activities worked across multiple phases and also connected with producers. A common strategy was creation of hubs that combine supplying production inputs with services and facilities related to aggregation, processing, market information, and connection with buyers. For example, as part of Feed the Future Partnering for Innovation (P4I), in Mozambique, the Export Marketing Company Limited uses retail hubs to offer services for grain storage facilities, marketing, inputs, a mobile platform for information, and equipment rental.

Figure: Number of Feed the Future activities operating in each value chain phase

The landscape analysis also collected information about the activities’ approaches to gender integration. Only about one-fourth of the interventions covered in the landscape analysis had readily accessible sex-disaggregated data to show women’s and men’s involvement. Women were most often reached by business development, marketing and processing efforts. Although data were not robust, there is indication that Feed the Future efforts expanded the size and scope of participating women’s enterprises and marketing opportunities. A small number of activities also reported increases in women’s sales, incomes and decision-making power within agricultural businesses or associations.

For example, in Bangladesh the PROSHAR project trained farmers in bulking and increased women’s market access through the establishment of collection points for aggregating and selling produce, which were more accessible to women than markets. PROSHAR also took active steps to connect female producers to other value chain actors through the formation of networks. The program found that 73 percent of female beneficiaries were bulking their produce and that 50 percent of collection point users were female.

Another example is FED in Liberia, which facilitated linkages, including 20 formal contracts in 2014, between farmers and market women through events to bring these value chain actors together. FED also linked predominantly female trade associations with supplying farmers.

As Feed the Future moves forward, we need to continue to improve collection, reporting and use of sex-disaggregated data, especially to capture women’s and men’s involvement in input and service provision, post-harvest handling, and processing and marketing, as well as the control and use of the income generated by these activities. We need to make sure we clearly identify how both women and men are benefiting from their own work!

The deeper understanding that comes from a robust review of evidence and lessons learned will allow for more rigorous identification of good practices that enhance women’s, men’s, boys’, and girls’ livelihoods and well-being throughout agricultural systems. As we break down barriers and facilitate access and expanded roles for women and men across agriculture and food systems, this analysis will allow us to understand not only what works (and what doesn’t!) but also where we need to go next. Together, we can realize Feed the Future’s continued commitments to inclusive agricultural growth, gender equality, and women’s empowerment.